Last month I wrote about the history of character education in American schools and drilled down to the character traits and values the Basic Education Act in our state outlined as important for schools to teach. One of these values is the concept that family is the basis of society. In other words, family is the foundation upon which our society is built. Let’s check in on the state of American families from yesteryear to today to see how our foundation is holding up.

Last month I wrote about the history of character education in American schools and drilled down to the character traits and values the Basic Education Act in our state outlined as important for schools to teach. One of these values is the concept that family is the basis of society. In other words, family is the foundation upon which our society is built. Let’s check in on the state of American families from yesteryear to today to see how our foundation is holding up.

According to Pew Research, in the 1960s, almost 73% of children were being raised in intact homes with their parents of origin. Today, only 46% of our students are coming from home where they have an intact family of origin. Not to put too fine a point on it, but this means over half of the children in our classrooms have felt the trauma of family break up and may be grappling with the complexity of living in a blended family. How do we teach about the importance of family when literally, the majority of our students will not grow up in an intact family?

We could talk about the about the different family structures out there. Unfortunately, no matter how you spin the numbers, study after study shows children coming from an intact family of origin fare the best when it comes to behavior and academic achievement. There are exceptions to the rule, but society is not built upon exceptions; it is built on the norm. We need to help our students develop the skills they will need to participate in healthy family lives as adults.

One lesson to teach…maintaining an intact family takes self-regulation skills.

Many times I have told a student escalating in conflict to hit the “cool it” seat outside my door. There the student can sit in simmering anger, chose to practice the breathing reminders (or not) and simply take a moment. I check on them. Have they breathed? Are they ready to talk? It is not until they have cooled enough and breathed enough to talk and hear words that I go and sit with them. I hear them out. We talk about the pain and shame that usually was the root of the conflict. We talk about how good it was to get away for a moment to clear out thinking. We talk about what we could have done differently so the anger did not get so hot. We talk about many of the other self-regulation skills we have learned in class.

And then I ask, “Why do you think it is important to learn to manage your feelings and manage conflict?”

If the student is fresh to the experience of the “cool it seat” they replay with, “So I don’t get in trouble.” That is true; for now. Back to class the student goes.

My repeat offenders hear an additional lesson. They hear a variation of the following:

“Hey, we seem to meet out here a lot. I am thinking I need to let you know a secret of life. Think you’re ready for a secret?”

What kid doesn’t like an insider secret? There is almost always a nod or at least a shrug of “Whatever” that really translates in my teacher’s mind to, “Please, give me the secret to ending this. I need to stop doing this same dumb thing. Help me out.”

I pull my chair closer and lean in. All kids know the best secrets are told leaning in.

I begin. “The thing is this. You do not magically get handed a pamphlet on how to handle anger and frustration when you are handed your child in the hospital. You do not get handed a book about how to love someone when you get married. If you think your own child or your wife someday could never make you as angry or frustrated as your classmate, you are beyond wrong.”

Repeat Offender just stares back. Still listening, but not hearing it yet.

“How mad that kid made you by taking your pencil and lying about it? That is nothing compared to your own 15 year-old sneaking out and lying about it. If you think for a moment that your wife won’t make you want to slam your fist through the wall from sheer frustration, you don’t get what loving and living with someone for a long time means.”

Repeat Offender usually says something snarky about not having kids or not being married. I always look them straight in the face and simply say, “True, but you are a kid. So, maybe you know how it feels to have a parent out of control…”

Most of the time there is a small wince. I hate that wince. It means they know.

“You job at this age is to learn to manage your emotions and your actions so that someday you have the skills to deal with your child without treating them like you just treated your classmate. You are here to learn how to keep your fist unclenched and at your sides instead of into walls. You are here to learn to hear the words of someone else, even when you are mad at them.”

Repeat Offender nods.

“Do you know why you need these skills?”

Repeat Offender knows somewhere in his heart, but does not know how to say the words.

I help. “You need the skills of self-regulation so you can have a happy life. So you can have a happy family.”

There is not a lesson I can teach about family being the basis of society. There are only moments I can grasp as teachable. If even one of my Repeat Offenders hears me and takes their need to learn self-regulation to heart, it is one more chance for a family to be kept intact in a healthy way. Healthy families are the basis of a healthy society.

*For the record, physical and emotional violence are not the only causes of families to fall apart. There are many other ways in which self-regulation plays a role in creating healthy family dynamics. There are also many other ways I teach self-regulation. Those will be the subject of my next blog as they connect to the other areas teaching character and values in the classroom.

It takes a little knowledge to dig a little deeper sometimes. This month, I am hitting the knowledge. Next month – I am digging a little deeper. What am I talking about? Character education! Let’s first get a little history…

It takes a little knowledge to dig a little deeper sometimes. This month, I am hitting the knowledge. Next month – I am digging a little deeper. What am I talking about? Character education! Let’s first get a little history…

The new year is upon us, happening too fast, as usual. Just as we get used to the schedule of a Winter Break, we are trying to get a mountain of tasks done before school starts up in a few short days. Where does the time go?

The new year is upon us, happening too fast, as usual. Just as we get used to the schedule of a Winter Break, we are trying to get a mountain of tasks done before school starts up in a few short days. Where does the time go? As I write this, my home is filled with the savory aroma of black-eyed peas, collard greens, and pork. It’s a tradition in our family, and in many places around the country, to eat black-eyed peas on New Year’s. It’s for luck and prosperity in the new year.

As I write this, my home is filled with the savory aroma of black-eyed peas, collard greens, and pork. It’s a tradition in our family, and in many places around the country, to eat black-eyed peas on New Year’s. It’s for luck and prosperity in the new year.  Don’t get me wrong; we need all of the supports mentioned in the proposal. We need more counselors in our buildings. We need plans for school safety that are actionable. We need all educational personnel to be trained to recognize and respond to symptoms of emotional distress. But, does anyone take time to wonder how we could prevent getting to the point where we are responding to distress?

Don’t get me wrong; we need all of the supports mentioned in the proposal. We need more counselors in our buildings. We need plans for school safety that are actionable. We need all educational personnel to be trained to recognize and respond to symptoms of emotional distress. But, does anyone take time to wonder how we could prevent getting to the point where we are responding to distress?

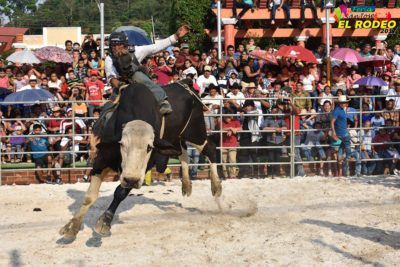

My New Year’s resolution is to not find myself on a bull ride with a student. In bull riding, an eight second ride earns the intrepid rider a spot on the scoreboard. It is intense and tough to do. In teaching, eight seconds can earn your student a chance at learning and you a chance at teaching.

My New Year’s resolution is to not find myself on a bull ride with a student. In bull riding, an eight second ride earns the intrepid rider a spot on the scoreboard. It is intense and tough to do. In teaching, eight seconds can earn your student a chance at learning and you a chance at teaching.