Censorship Gone Wild

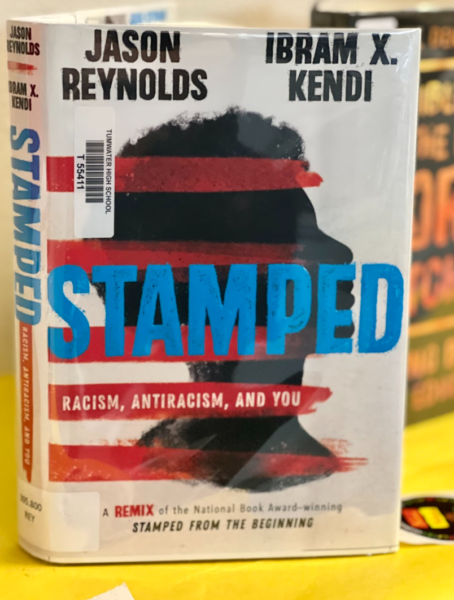

There have been a plethora of school library censorship and banned book stories lately. Unfortunately ,there are too many to list, but here are a few highlights that may have graced your news feeds.

A school district in Tennessee banned the graphic novel Maus by Art Speiglman over concerns of profanity and female nudity.

Another in removed Toni Morrison’s first novel, The Bluest Eye from library shelves for obscenity.

Texas, perhaps unsurprisingly, has a whole host of books their officials want to ban, an overwhelming amount of which feature LGBTQ+ characters and themes.

Librarians have been accused of poisoning young minds, buying pornography, and indoctrinating students.

In the midst of all of this, it would be easy for Washington educators and librarians to rest on our laurels, grateful not to be working in one of these states with high profile cases. After all, Washington is liberal and progressive, right?

But, when a colleague sent me this article on Book Riot, “LGBTQ+ Books Quietly Pulled from Washington State Middle School” I was reminded that issues of intellectual freedom and censorship in school libraries are everywhere. Stories like this one that don’t make national headlines are even more unsettling for their insidiousness.

In Our Backyard

In Kent, The Cedar Heights Middle School librarian, Gavin Downing, was deemed to have “sexually explicit” books on his shelves. The principal pulled books from the shelves, insisted that she monitor all future purchases, and created a council at school to advise Downing on “age appropriate material.”

It all started with Jack of Hearts by L.C Rosen about an “unapologetically queer teen” who “celebrates the freedom to be oneself, especially in the face of adversity.” If I Was Your Girl by Meredith Russo, an award winning novel about a trans girl, and All Boys Aren’t Blue, a memoir by LGBTQIA+ activist George M. Johnson, were also discussed at board meetings and removed.

Kent has a board policy to “revolutionize school libraries” across the district but clearly, censoring queer voices is out of alignment with the third phase of their plan which seeks to “reinforce equity and excellence.”

I can’t help but draw parallels to Texas where 59.95% of the 850 books on the governor’s banned list feature LGBTQ+ characters.

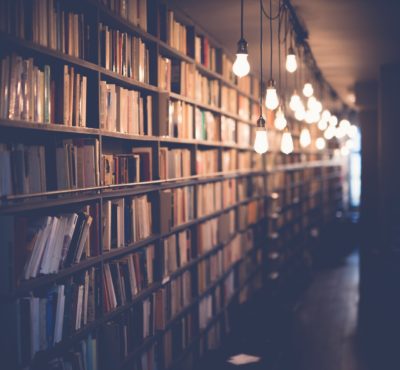

In Defense of Libraries

I am an English teacher, so it’s perhaps unsurprising that I take the freedom to read very seriously. I have also been unspoken about the fact that I think we need to update our curriculums to reflect a more accurate, diverse, and empathetic world view.

Additionally, this year, I’ve been a librarian half the day, a move that has encouraged me to pursue my library media endorsement, with the hopes of becoming a full time school librarian.

In preparation for one of my classes, I researched Library Bill of Rights and the American Library Association makes it clear that the principles of the bill apply to school libraries.

The ALA has a series of interpretations of this bill and there are a few principles that stood out to me in regards to both local and national censorship.

Intellectual Freedom: School librarians are leaders in promoting “the principles of intellectual freedom,” and must empower students with “critical thinking skills to empower them to pursue free inquiry responsibly and independently.”

In the Cedar Heights Middle School case, the removal of books from library shelves limits free and independent inquiry. Remember, we aren’t talking curriculum here, but simply books that students have the freedom to read on their own time.

Diverse Points of View: Collection material should “represent diverse points of view on both current and historical issues” and “support the intellectual growth, personal development, individual interests, and recreational needs of students.”

Representation matters. Books by and about the LGBTQ+ community can be powerful mirrors into students’ own experience or windows to foster empathy. I’d argue the titles that were removed from Cedar Heights could have played an integral role in students’ “intellectual growth” and “personal development.”

Political Views: The resources in the library should not be constrained by “personal, political, social, or religious views” and school librarians should resist efforts of outside groups to “define what is appropriate for all students or teachers to read, view, hear, or access.”

It’s no coincidence that the books banned in Kent were all written by and about members of the LGBTQ+ community. As long as those individuals continue to face discrimination, their existence and their stories will remain politically charged.

Rights of Minors: “Children and young adults unquestionably possess First Amendment rights, including the right to receive information through the library” and equitable library access should not be abridged by “chronological age, apparent maturity, educational level, literacy skills…”

Librarians are tasked with using their expertise in areas of literacy and adolescent development to fill their shelves. They are uniquely positioned to help their patrons explore those materials and think critically. Students are exposed to more than ever before online, and libraries are a safe place for them to explore a variety of resources with the guidance of a caring adult.

Parental Responsibility “Parents and guardians have the right and the responsibility to determine their children’s—and only their children’s—access to library resources. Parents and guardians who do not want their children to have access to specific library services, materials, or facilities should advise their own children.”

While I can see why some content might be deemed too mature for young readers, all of the books facing removal at Cedar Heights are highly vetted, award winning, and deemed important young adult texts. As an educator who has, at times during this pandemic, felt more like a babysitter than a teacher, I very much appreciate the focus on families’ individual choices.

What’s Next?

I wish I had answers during these “polarizing” and “unprecedented” times. Maybe, some day, we can live in a more harmonious political climate and experience some mundane, precedented news stories, though I’m not holding out hope.

However, as an educator, English teacher, and aspiring school librarian, it’s clear to me that the challenges we’re facing around intellectual freedom warrant our full attention.

So, pay attention to your school library and the books filling it’s shelves. Does your librarian curate a collection that is representative of your students’ needs?

Tune into your local school board meetings and contact the members. (The Book Riot article has contact information for Kent board members if you want to help the situation in Cedar Heights ).

Have conversations with your principal and colleagues. Where do they stand on issues of censorship and equity?

Our students deserve the freedom to read and we should never stop fighting for that right.

Civil discourse is the engagement in conversation to enhance understanding. It requires respect for all others involved, without judgment. You cannot conduct civil discourse if it is obvious that you question the good sense of your peers. You cannot conduct yourself with hostility, sarcasm, mockery, or excess persuasive language. You have to accept the views of others as valid, despite your disagreement.

Civil discourse is the engagement in conversation to enhance understanding. It requires respect for all others involved, without judgment. You cannot conduct civil discourse if it is obvious that you question the good sense of your peers. You cannot conduct yourself with hostility, sarcasm, mockery, or excess persuasive language. You have to accept the views of others as valid, despite your disagreement. As teachers, the urge to stay out of it, to be apolitical and neutral is strong. We don’t want to offend our students, their families, or our communities. However, we must model that we all have views and ideas, and how we express them is important. We do not force our views on others, but, instead, we invite discourse. Our students need to learn to share their ideas and listen to their peers. They need to understand the importance of researching the issues and verifying their sources. They need to practice protocols of debate and dialogue that guide them to be supportive listeners, even when they disagree.

As teachers, the urge to stay out of it, to be apolitical and neutral is strong. We don’t want to offend our students, their families, or our communities. However, we must model that we all have views and ideas, and how we express them is important. We do not force our views on others, but, instead, we invite discourse. Our students need to learn to share their ideas and listen to their peers. They need to understand the importance of researching the issues and verifying their sources. They need to practice protocols of debate and dialogue that guide them to be supportive listeners, even when they disagree.