I received several emails from my son’s science teacher warning of the upcoming evolution unit, clarifying the goals of the unit, and offering opt-out pathways. I’ve long understood such disclaimers and options as being due to the reality that evolution as it relates to humankind does not mesh well with some religious cosmologies. The concept of the current biological state of humanity being a phase in a billion-year-long slow-and-steady march of natural variation does not match what many people believe.

So what happens when we go to teach current events, American history, civics and government, or other social sciences and students or families want to opt out because it does not match what they believe?

Continue reading The minute my mom was diagnosed, a quarantine poster was slapped on the front door of their house. When her dad came home from work, he wasn’t allowed inside his own home. That’s how seriously they took quarantines in 1938.

The minute my mom was diagnosed, a quarantine poster was slapped on the front door of their house. When her dad came home from work, he wasn’t allowed inside his own home. That’s how seriously they took quarantines in 1938.

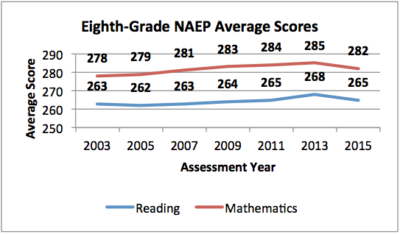

In fact, this backwards system of integration may explain why reading scores have flatlined since 1998!

In fact, this backwards system of integration may explain why reading scores have flatlined since 1998! I teach middle school in the upper reaches of NE Washington. In our district, let’s just say there are a certain number of families where the belief is that Scientific Theories are “just theories…” and “scientist are always changing their minds on stuff – why should we believe in them at all?” Both of these widely held and openly expressed sentiments are easily corrected in my classroom with lessons on the definition of scientific theory and the nature of science being that of change. Yet, with the words, “My grandpa says you’re a liar. There is no climate change – it is just the weather,” blurted out from a freckle-faced middle-schooler ringing in my mind, it does not always feel a real easy space and place for the exploration of evolution, carbon footprints, and the beginning of a Universe based on physics.

I teach middle school in the upper reaches of NE Washington. In our district, let’s just say there are a certain number of families where the belief is that Scientific Theories are “just theories…” and “scientist are always changing their minds on stuff – why should we believe in them at all?” Both of these widely held and openly expressed sentiments are easily corrected in my classroom with lessons on the definition of scientific theory and the nature of science being that of change. Yet, with the words, “My grandpa says you’re a liar. There is no climate change – it is just the weather,” blurted out from a freckle-faced middle-schooler ringing in my mind, it does not always feel a real easy space and place for the exploration of evolution, carbon footprints, and the beginning of a Universe based on physics.