I was numbly scrolling through Facebook a recent morning when one of those infographic-ish memes appeared. Of course, since it was in my feed, it aligned with the political leanings that my clicks and likes had already communicated to the Facebook algorithms, and in my pre-coffee state I found myself hovering over the “share” button.

I had to pause, though. Even though I wanted (desperately) to believe that the political statement being made in the meme was true (hint: it had to do with golf trips and certain federal budget items), I wasn’t sure. I didn’t see any sources linked, I didn’t know who the creator of the meme was, and I didn’t want to spend a ton of time researching its veracity. I did anyway, and after about three minutes of research it turned out that this particular meme had its number off by about 100 times and misrepresented the nature of the budget in question. Darn those pesky alternative facts.

While I didn’t click “share,” that nugget of information, despite being proven false, is now lodged in the schema that I bring to political conversations in the near future. I will have to very intentionally not use it as I form my arguments to support my political positions. That will be hard, because meme-depth facts are what it seems most political conversations resort to anymore.

We hear plenty about Fake News nowadays. Fake News is to critical thinking what super-sized fast food is to our diet: It is convenient, appears to look more or less like it’s authentic counterpart, and satisfies a need. Yes, a flawed analogy if extended completely, but there are valid parallels about the long term health of both individuals and the community. In particular, a good parallel is that the amount of comparable effort it takes to systematically deconstruct and discount Fake News is as seemingly insurmountable as making seismic shifts to unhealthy diet habits. If the latter were easy, we’d all be fit and healthy; if the former were easy, Fake News would be a nonissue.

How do we teach “quick” critical thinking? How do we teach students to resist the temptation of our confirmation biases? How do we teach that facts aren’t established by clicks, shares, or re-tweets…and that our own opinions don’t trump facts just because our opinions are our own?

Forget Common Core. This is the great pedagogical challenge of the next phase of my career.

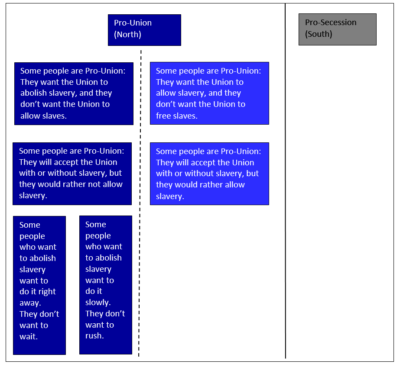

But Lincoln didn’t stop there. He went on. “It is easy to conceive that all these shades of opinion, and even more, may be sincerely entertained by honest and truthful men.”

But Lincoln didn’t stop there. He went on. “It is easy to conceive that all these shades of opinion, and even more, may be sincerely entertained by honest and truthful men.”

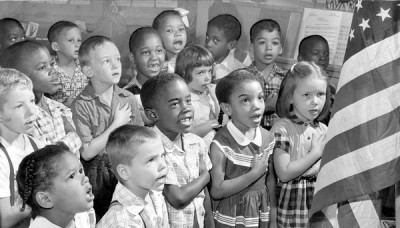

This post is the beginning of a series of posts I will write about 21st century school segregation. I want to start by acknowledging a few factors that influence my perspective and shape my writing.

This post is the beginning of a series of posts I will write about 21st century school segregation. I want to start by acknowledging a few factors that influence my perspective and shape my writing.