The Hyatt filled with teens from across the country. The smell of long bus rides, airplane food, and hot Cheetos permeated the lobby. But by the opening session, these students had transformed into professionally dressed young men and women in “conference mode.” Their excitement and energy was palpable in the North Ballroom. Last weekend was the convergence of young voices at the Educators Rising Annual Conference. This organization “cultivates highly skilled educators by guiding young people on a path to becoming accomplished teachers, beginning in high school and extending through college and into the profession.” What’s even more exciting than this mission is that 51% of the 30k members are students of color!

Basically, Educators Rising works with secondary teachers to identify black, brown, and white young people–as young as 13– who have potential as future educators. Through intentional programming at local and state levels, these students will one day be well-prepared, highly effective classroom teachers. The annual conference offers outstanding keynotes, interactive workshops on cultural competency and teacher leadership, and competitions.

Competitions are fascinating and are divided into three categories:

- Teaching. Sub categories include planned instruction where students create a lesson, tape themselves teaching, then reflect with a judge (think National Boards) or impromptu teaching where a student is given a scenario (Mr. Hall started vomiting and you must take over his class immediately), a learning standard, and a box of materials. The subs must create an engaging lesson and deliver it in a short time (think Iron Chef but teaching).

- Career Explorations. Students competing in this category follow an administrator, a non-core classroom teacher, or a support staff member in a job shadow. They must conduct an interview, dig into all aspects of this career and then present their findings..

- Advocacy and Policy Development. Students can create a Ted Talk on an effective instructional strategy, present a policy brief on a researched issue, or give an impromptu speech on an education issue.

Are you kidding me!? I know grown adults who couldn’t handle these challenges.

This makes me hopeful.

Early in the opening session, Joshua Starr set the tone of the conference when he quoted Dr. King reminding us that “the arc of the moral universe is long but it bends towards justice.” Despite our political climate, the increase in police brutality, and the growing racial divide in this country, we must still have hope. Nate Bowling developed this theme with his talk that culminated in a challenge for everyone in the room (current or future educators): Embed, Disrupt, and Advocate.

Nods, tweets and follow up conversations indicated that these messages resonated with the crowd. This makes me hopeful.

While some adults complain about teens obsession with fidget spinners and Snapchat, I’m here to tell you that our young people are far better than we are. They are more creative. They are more compassionate. They are more understanding. They are more kind. They are more justice-minded.

I met two students who especially exemplified these qualities—Educators Rising National Student President, Cassey Hall from Mississippi and National Student Officer Tamir Harper from Philadelphia. Cassey shared her story of how her 9th grade English teacher recruited her into a new course centered on learning about teaching. As she heads off to college, she is certain she wants to be a 3rd grade Science teacher.

I struck up a conversation with Tamir on the way out of the convention center. Instantly I was struck by his charisma, his wisdom, and his passion for his school, his neighborhood, and his city. Besides running a session at the conference on reconstructing the educational system, this fall Tamir will co-teaching an African American history class at his high school. As Tamir shared his dreams to teach and later run for office, I kept think “is this young man really 17?!”

These are just two of the hundreds of students at #EducatorsRising17 that I know are bending their voices towards justice. In four to six years, they will be teaching our children. I cannot wait!

They make me hopeful.

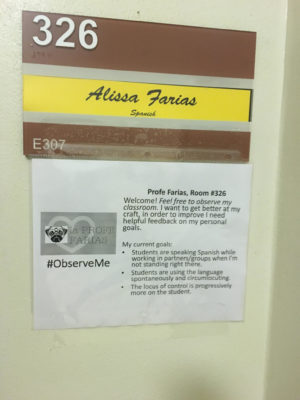

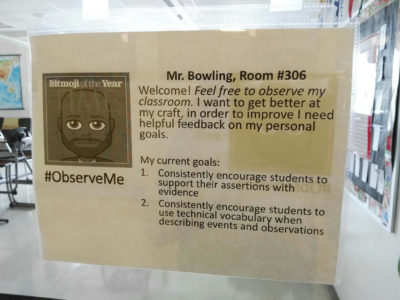

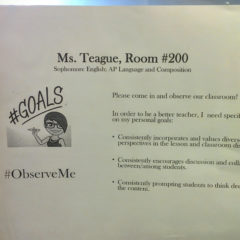

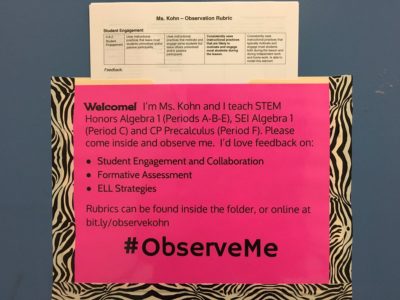

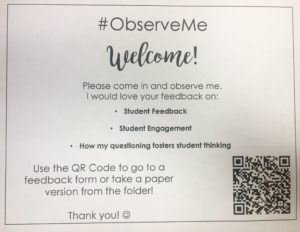

It forces me to have a growth mindset. If this sign is on my door, I am telling the world that I want to grow. I am inviting anyone to come in and comment on my instruct. Yeah, that’s a little scary. But it’s a healthy risk that models vulnerability and openness to others. Who could pop in? A visitor. A parent. The librarian. Another teacher on planning period. I’m both thrilled and terrified at the possibilities. The #ObserveMe challenge reminds us that teaching is relational and we need all types of perspectives to help us grow. This model is based on trust. By opening myself up to the community, I am making them a part of my learning process and saying that I value their voice in my growth.

It forces me to have a growth mindset. If this sign is on my door, I am telling the world that I want to grow. I am inviting anyone to come in and comment on my instruct. Yeah, that’s a little scary. But it’s a healthy risk that models vulnerability and openness to others. Who could pop in? A visitor. A parent. The librarian. Another teacher on planning period. I’m both thrilled and terrified at the possibilities. The #ObserveMe challenge reminds us that teaching is relational and we need all types of perspectives to help us grow. This model is based on trust. By opening myself up to the community, I am making them a part of my learning process and saying that I value their voice in my growth.