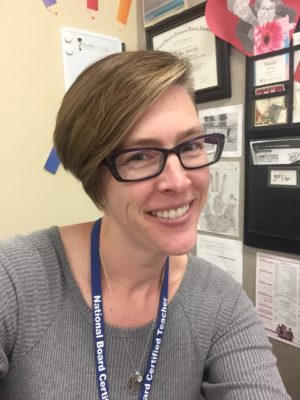

With the recent news that 1,435 teachers recently earned National Board Certification and 533 teachers renewed National Board Certification, the State of Washington has much to celebrate. This achievement means a great deal to the teachers, districts, cohorts, and our state education system, including a variety of agencies and organizations that provide supports to those seeking certification. However, for those who’ve just earned certification, your race to the finish line might feel it’s over, but In fact, it’s just beginning.

Thirteen years ago I began my National Board Certification journey. I was a fourth year teacher, both new to Washington and my district. I was the first in my district to attempt certification much less complete the process. I remember trying to explain it to my students–many had never seen a video camera in the classroom before. Most people in my district hadn’t heard of this certification, much less how to support it. I struggled through the certification process without the supports that exist in the system today, but with the mindset that I would finish what I started. And I did. In all transparency, I barely made it and certified by one point. That one point might have made the difference between certifying in 2005 versus 2006 but the process involved created more growth for me than just arriving at the destination. After certifying, I took on a challenge. I wanted to open the doors for other teachers to deeply analyze their practice using the structure and framework provided by the National Board process. This is where my leadership began. I wanted to be the person who helped clear the pathways so that others who wanted to, could travel with a bit more ease. Thirteen years later, I’m proud to say that my district has many National Board Certified Teachers and an effective cohort system that supports teachers and counselors as they journey down this road.

I oftentimes share with candidates that the process of earning National Board Certification is more of a marathon and less of a sprint. Figuring out when to start the race depends on the individual teacher/counselor. There is no perfect time to start. I started the process at a critical time in my career. I was just past the triage stage–you know, when you’re staying up until midnight planning for tomorrow’s lesson, unsure of where you’re going or how to get there. Now, I could see the big picture and better understand my pacing, skill development, and how to write assessments. But I certainly didn’t feel settled. I needed National Board Certification to push me, to develop me, and to help me find more rhythm. I questioned the triage strategies and routines I’d already established. I needed this, like a runner needs fuel. Analyzing my work fed my soul and honed my skills to make me a reflective practitioner.

The growth didn’t just come from the process. Certification was a pivotal turning point in my teaching career. Who knows, perhaps it was the one point differential that activated change in me. Perhaps it was the adrenaline rush that comes from finding out that I certified. But after learning that I certified, I began to see myself as a teacher leader. I became more involved in organizations that promote and support highly effective teaching practices. I began advocating for students at a building and district level. I understood that my voice could be heard and that my personal struggle through the process brought validation and credibility to the table when I talked with administrators about the needs of students. I took on more leadership roles, participated in building decision making, and felt inspired to be a change agent for my community. I took risks–used cutting edge resources, created new lessons, developed new strategies and all the while, reflected upon each change to determine what worked, what didn’t, and why (a process I practiced through National Board and continue to use today). And while many of my colleagues who aren’t NBCTs may be doing these things too, this certification caused me to go down this path. The best part is, that my journey into teacher leadership is still ongoing. Like so many other NBCTs, my race isn’t over yet. Heck, we’re just now picking up speed.

I laid awake in bed at the Omni Shoreham. Light seeped through the cracks of the door and laughter drifted up from the courtyard. It wasn’t so much the time zone that kept me awake. I couldn’t turn my brain off. I often can’t turn my brain off.=

I laid awake in bed at the Omni Shoreham. Light seeped through the cracks of the door and laughter drifted up from the courtyard. It wasn’t so much the time zone that kept me awake. I couldn’t turn my brain off. I often can’t turn my brain off.=