My teacher leadership journey has evolved from an inability to say no to a training, a committee, or an extra responsibility, into an ongoing urge to seek out new and innovative opportunities for learning. It’s not a journey that suits everyone, but, for me, constant growth and learning is as integral as the air I breathe. So, I keep looking for the next teacher leadership opportunity around the bend.

This summer I received the news that I was chosen for the Fulbright Teachers for Global Classrooms program (TGC). This wonderful opportunity will allow me and my cohort of 75 other teachers around the country to travel next spring to visit teachers overseas. Of course, I’m thrilled! I am always looking for ways to broaden my horizons as a teacher, and going “global” seems like the ultimate leap forward.

The program requires me to complete a course of study in global competence in the classroom, and, one week in, I am completely blown away. I feel like a whole world of teaching skills and strategies has opened up to me. I feel both validated in my beliefs as a teacher and severely challenged in my methods. It’s, well, a sea change for me.

Let me catch you up. I will use elements from ASCD’s Global Competent Learning Continuum to explain. This is a rubric that measures a teacher’s global competencies. You can explore the full continuum here.

Teacher Dispositions

1. Empathy and valuing multiple perspectives

2. Commitment to promoting equity worldwide

When it comes to the the dispositions outlined by the continuum, I find myself approaching “proficient.” That means that I see myself as actively recognizing biases and the limitations of my own and others’ perspectives. Also, I actively engage in activities that address inequities, often challenging myself and others to seek change at a local or regional level. I felt pretty good about this area, although I could see that to become advanced in a global teaching disposition, I would have to lead others to value diverse perspectives and act on issues of inequity. I need to step up my game.

Teacher Knowledge

3. Understanding of global conditions and current events

4. Understanding of the ways that the world is interconnected

5. Experiential understanding of multiple cultures

6. Understanding of intercultural communication

In the area of Teacher Knowledge, I am approaching proficient as well. I pride myself on being educated and aware, of pursuing knowledge and understanding of history, current events, and social issues. However, I recognize a glaring weakness in my competency. I don’t see myself as capable of change or leadership beyond a local level. Even though I tell my students that they can enact change, that they have the power to create a better future for themselves and our world, I am not walking the walk. I merely talk the talk. Continue reading

So what is this “bushel basket” all about? It’s from the New Testament. In the King James version Matthew 5:15 says, “Neither do men light a candle, and put it under a bushel, but on a candlestick; and it giveth light unto all that are in the house.” Now, historically, a bushel was a container for goods, such as grain, that became a unit of measure. So this is a bit weird in modern terms. But you get the idea. In this context, the light could be your faith, but it can also be your wisdom, your learning, your spark. Why hide a light?

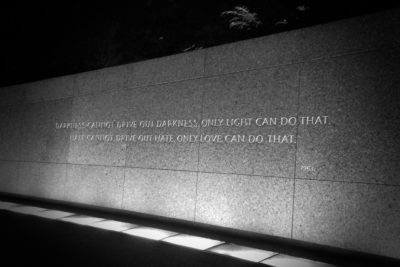

So what is this “bushel basket” all about? It’s from the New Testament. In the King James version Matthew 5:15 says, “Neither do men light a candle, and put it under a bushel, but on a candlestick; and it giveth light unto all that are in the house.” Now, historically, a bushel was a container for goods, such as grain, that became a unit of measure. So this is a bit weird in modern terms. But you get the idea. In this context, the light could be your faith, but it can also be your wisdom, your learning, your spark. Why hide a light? Now let me take this a step further. Where there is light, there is darkness. And let’s face it; there have been some dark moments in our schools recently. There are dark issues faced by our students and our colleagues. To fight the darkness, we need to rally behind the light. We teachers can do so much to help our students as they face the future, as they become the problem-solvers of tomorrow. As Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., famously said, “Darkness cannot drive out darkness; only light can do that. Hate cannot drive out hate; only love can do that.”

Now let me take this a step further. Where there is light, there is darkness. And let’s face it; there have been some dark moments in our schools recently. There are dark issues faced by our students and our colleagues. To fight the darkness, we need to rally behind the light. We teachers can do so much to help our students as they face the future, as they become the problem-solvers of tomorrow. As Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., famously said, “Darkness cannot drive out darkness; only light can do that. Hate cannot drive out hate; only love can do that.”

I’m currently struggling with such a dilemma. Our district is strenghtening its retention policy to discourage a rapid uptick in junior high students with failing grades. The majority of district staff believe that if our policy has more “teeth,” if we actually retain more students, then others will work harder. This issue strikes a very harsh chord with me, and it’s personal.

I’m currently struggling with such a dilemma. Our district is strenghtening its retention policy to discourage a rapid uptick in junior high students with failing grades. The majority of district staff believe that if our policy has more “teeth,” if we actually retain more students, then others will work harder. This issue strikes a very harsh chord with me, and it’s personal.