“Oh you’re a teacher! You guys have it made. Paid summers off where you sleep in every day–what a cushy life.” These words, uttered by my dentist while his hands were in my mouth drilling a tooth, caused far more discomfort than the actual dental procedure. So after he was done  (and yes, the novocaine still had half of my face numb) I shared with him that I spent most of my summer at conferences and in classes. I also explained how the pay structure works. And, as these conversations typically go, it ended up with, “I really had no idea.”

(and yes, the novocaine still had half of my face numb) I shared with him that I spent most of my summer at conferences and in classes. I also explained how the pay structure works. And, as these conversations typically go, it ended up with, “I really had no idea.”

A year ago I felt a fire light inside me. I can’t remember what started it all to build, but the result has been an overwhelming desire to advocate for the teaching profession. Maybe it was the need to address the misconceptions that people have about this lifestyle (I consider teaching a lifestyle, it’s far too encompassing to just be a job) or perhaps it was the oversimplification of this work by the media, tv shows, and movies that show burned out teachers, but either way, that fire started and it keeps burning brighter.

So last week, when the airplane pilot standing next to me on the shuttle to our plane started asking me questions about my work, I was happy to share the dynamic nature of teaching. I also made sure to note that I was flying back from a week long class on constitutional law. The pilot didn’t realize that teachers participate in summer coursework to strengthen their knowledge and skills in the classroom. He was curious about this and we had a great conversation (our shuttle was stuck on the tarmac for 30 minutes) about professional development for teachers and pilots, thus shedding light on both of our professions.

I have spent the past eight months talking to policymakers and stakeholders about the impact of legislation in the classroom. While I go in with a game plan, inevitably the conversation always turns when I tell a story about my students, my colleagues, and my own children. Last month I met with my US Congresswoman in Washington D.C., and while my ask was to retain Title II funding in the budget, my story was specific to how we use that funding in our schools. This story provides insight into policy impact and also constituent needs. Her job is dynamic, too, and I do not expect my representative to be an expert in all facets of life. So if I can be a resource and share my experience with her, then perhaps that experience can shape her thinking on an issue.

I’ve come to see these interactions as opportunities to educate and advocate for this work. We can control the narrative. It’s easy to sell an anti-teacher message when the public doesn’t have a deep understanding of what our work looks like. Worse, if people rely upon their varied past experiences as students without recognizing how that skews their vision of what schools look like today, the picture that’s created may likely be inconsistent in practice and unrecognizable to those of us who do teach. So instead of dismissing ignorant remarks about our work, it is imperative that we seize the moment as an opportunity to teach. We must teach others about our work so that they can see the intricacies of this lifestyle. We must share our stories, our experiences, our successes, and our struggles. Only then will the larger public begin to see who we really are.

If your school is anything like mine, you’re about to enter Testing Season. We come back from Spring Break, get reorganized and start gearing up for the SBAs. We review important material and have our students take practice tests on their computers. We teach test-taking strategies and emphasize the importance of sleep, diet and attendance.

If your school is anything like mine, you’re about to enter Testing Season. We come back from Spring Break, get reorganized and start gearing up for the SBAs. We review important material and have our students take practice tests on their computers. We teach test-taking strategies and emphasize the importance of sleep, diet and attendance.

er learning. Yet, it didn’t occur to me until recently to build a bridge. Perhaps that’s what my work is now. I’m an engineer–creating bridges between my classroom and my state policymakers.

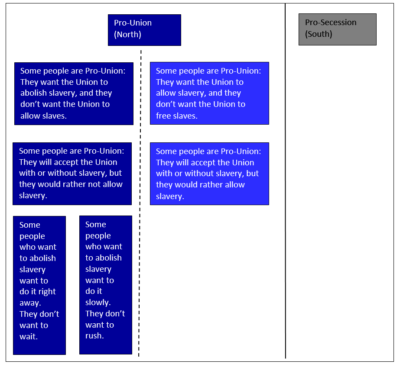

er learning. Yet, it didn’t occur to me until recently to build a bridge. Perhaps that’s what my work is now. I’m an engineer–creating bridges between my classroom and my state policymakers. But Lincoln didn’t stop there. He went on. “It is easy to conceive that all these shades of opinion, and even more, may be sincerely entertained by honest and truthful men.”

But Lincoln didn’t stop there. He went on. “It is easy to conceive that all these shades of opinion, and even more, may be sincerely entertained by honest and truthful men.” I had plans for last Wednesday.

I had plans for last Wednesday. I’ve been on more committees, task forces and planning teams than I care to remember. Many of them were productive and well worth my time. One particular team produced

I’ve been on more committees, task forces and planning teams than I care to remember. Many of them were productive and well worth my time. One particular team produced

Every National Board Certified Teacher has a story. This is mine.

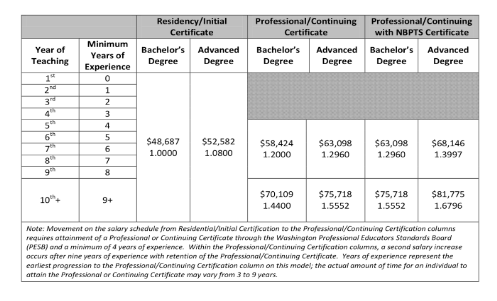

Every National Board Certified Teacher has a story. This is mine. In 1999 I was a relatively young National Board candidate. There were about 30 of us going through the process in our state, aspiring to join the seven or so Washington State NBCTs. Someone sponsored a reception in Seattle and then-governor Gary Locke was the featured speaker. While explaining his proposed 15% NBCT bonus, he remarked that someone in the Legislature asked him, “What if all of these candidates pass? How will we afford those bonuses?”

In 1999 I was a relatively young National Board candidate. There were about 30 of us going through the process in our state, aspiring to join the seven or so Washington State NBCTs. Someone sponsored a reception in Seattle and then-governor Gary Locke was the featured speaker. While explaining his proposed 15% NBCT bonus, he remarked that someone in the Legislature asked him, “What if all of these candidates pass? How will we afford those bonuses?”