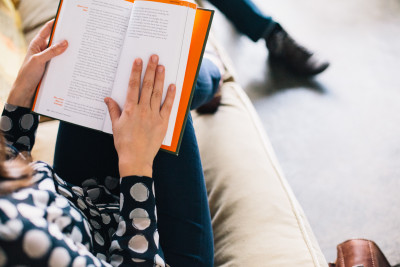

It always starts with a dream. A real dream; not an aspiration or goal, but the kind you have when you sleep. One year it was a poorly-executed field trip to Manhattan (with fourth graders) and another year I had a class of forty but no classroom. I was expected to teach them out on the lawn.

It always starts with a dream. A real dream; not an aspiration or goal, but the kind you have when you sleep. One year it was a poorly-executed field trip to Manhattan (with fourth graders) and another year I had a class of forty but no classroom. I was expected to teach them out on the lawn.

In this year’s late-summer teacher dream I was giving a practice spelling test to my kiddos and the third word on the list was “sh*t.” It was a difficult situation, especially trying to come up with an appropriate context sentence. I remember silently cursing the publishers from whom we adopted the curriculum.

My annual awkward teacher dream is how I know my summer is winding down. The next phase involves completely going over my plans for the year. Then there’s the “Leadership Team Retreat” where we revisit our School Improvement Plan and chart out corresponding Professional Development. After that there’s a few days of moving furniture and putting up bulletin boards, some whole-staff meetings, a slew of online, state-mandated health trainings and before I know it, kids.

But let me back up a bit, to the part where I go over my plans for the year. One thing I’ve noticed is that as the years go by, I find myself changing things less and less. Back in the day, I would practically reinvent myself every summer. Different homework plans, new classroom management programs, alternative seating plans, you name it. But now, thirty-three years in, I find myself merely tweaking.

When I first noticed this trend I felt lazy. Is this what it feels like to be burned-out old-timer? Perhaps. But maybe it’s what it feels like to be a competent veteran. I think about the major changes I used to make – classroom management, for example – and I honestly don’t feel compelled to make any major changes. Not because I’m afraid of the effort, but because it worked last year. And the year before that.

Change is good. But so is repeating something that still works. I guess the challenge is trying to figure out what to keep and what to tweak.

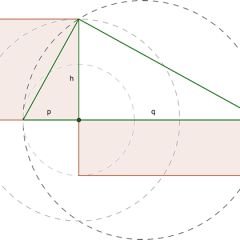

And believe it or not, the only thing I’m going to totally overhaul this year is my spelling curriculum.

I wonder why.

My youngest son recently announced he was thinking about becoming a teacher. “What are all the steps you have to go through?” he asked.

My youngest son recently announced he was thinking about becoming a teacher. “What are all the steps you have to go through?” he asked.

Senator Pam Roach introduced

Senator Pam Roach introduced