Washington State just welcomed 1,434 new National Board Certified Teachers. That makes 10,135 statewide. The popularity and support of National Board Certification indicates an emphasis on quality education for the students of our state. We are fortunate to have support at a level that teachers in other states can only imagine.

Suddenly, all around me, teachers are taking notice and asking about National Boards. What is it like? Should they do it? Is it worth it?

Good questions. I think I have some answers.

I am a National Board Certified Teacher. And that matters. Now let me tell you why.

NBCTs demonstrate a new levels of dedication to their students. Certainly, I was thoroughly dedicated before I certified, as are the majority of teachers. I was the sort of teacher that was always looking for ways to improve my practice. I wanted to be the teacher my students deserved. And I was willing to work for it. This is just the sort of teacher that decides to pursue certification.

It takes a certain work ethic to pursue certification, but the extra work is worth it if students benefit. When it’s all said and done, certification is a badge of honor, proof of dedication.

NBCTs take increasing pride in their work. And yet there is a certain humility that we cultivate as well. We know that everything we do is grounded in our knowledge of our students and their needs.

I was the first in my small, rural district to certify. Hardly anyone seemed to notice at the time. Despite that, I was overflowing with pride in my achievement and a new level of confidence.

That newfound confidence led me to do something bold on that very day. I was looking for my name on the National Board for Professional Teaching Standards website. I just wanted to make sure it was there, that I really was an NBCT. An announcement on the webpage caught my eye. The NBPTS was looking for applicants for its English Language Arts Standards Committee.

I had just certified…just that day. But did that keep me from filling out an application? No, it did not. And, by some miracle, I ended up on that committee.

With the NBPTS ELA Standards Committee, I had the experience of working with passionate and talented educators from around the country, creating standards that made us all very proud. The experience left me with a weird mixture of humble gratitude and elevated confidence in my abilities.

My certificate- A student’s reflection is visible, if you look closely. It has a place of honor in my classroom, as a reminder to keep my students at the forefront of my practice.

For many NBCTs, the journey doesn’t end at certification. NBCTs don’t retreat from the work. They know that we have to continue growing and improving as professionals, just as we want our students to grow and improve.

My professional journey has made me a much better learner alongside my students. I have learned to adjust on the fly, and to tweak activities and instructional tools to work for individuals, small groups, and whole classes. And, most of all, I know that we are all works in progress. My students and myself, we have a lot of growing to do. My NBCT journey gave me the confidence to always be in the middle of it, never just coasting on what I have always done before.

NBCTs develop the courage to look back and ask hard questions about their practice. We know what it is like to be judged by our peers, and, as unnerving as it is, the growth we achieve through the process propels us, perpetually looking back in order to move forward. The NBCTs I talk to always say that the certification process forces them to increase their ability to reflect and seek feedback. There is always something that can improve.

If you are trying something new, if you are pushing yourself to improve, you will find yourself in uncomfortable territory, where failure is possible. Not everyone is up to this, but NBCTs are ready to reflect and to adjust their practice as needed.

NBCTs seek opportunities to collaborate with others to provide the best experiences for their students. That means reaching out to their colleagues, their communities, their online resources and beyond. Our access to ideas and support is virtually limitless. For years, this pursuit of a network of support has bolstered my practice, increasing my confidence and filling my toolbox full of instructional tricks of the trade.

With the new interest in National Board Certification in my rural region, it became part of my journey to become a cohort facilitator and help others on their path to certification. Local cohorts like ours are making it possible to get rural educators on board.

This year, two of my colleagues certified; so there are three NBCTs in my district now, and five more candidates in the process. The fire that has been lit across the state has ignited in rural Lewis County after all.

So, if you or someone you know is considering National Board Certification, if you are wondering what all the fuss is about, let me tell you:

Through National Board Certification teachers validate their practice and gain confidence to take it to the next level. Certification begins a journey of professional development that can be richly rewarding.

I highly recommend it.

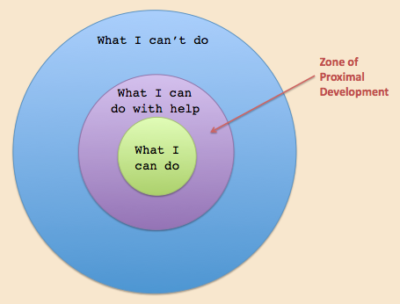

Think of putting fourth graders into first grade classrooms. That would be ludicrous, right? While the teacher is working with the first graders on “What I can do with help,” the fourth graders are well past the “What I can do” and into the “I’m bored and trying to amuse myself” zone.

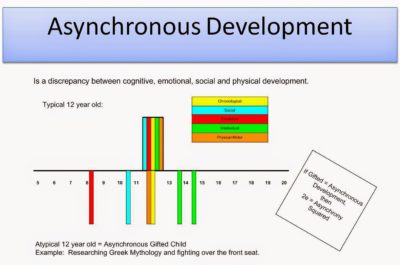

Think of putting fourth graders into first grade classrooms. That would be ludicrous, right? While the teacher is working with the first graders on “What I can do with help,” the fourth graders are well past the “What I can do” and into the “I’m bored and trying to amuse myself” zone. Every year I have several students who are academically advanced but who are socially and emotionally immature. In some cases very immature. One of the defining characteristics of gifted is “asynchronous development.” Gifted students are out of the norm in terms of their development when compared to their age peers. That can mean they are out of the norm in more than just the realm of intellect. Which is why you can have a fifth grader working at the intellectual level of a 15-year-old but acting emotionally like a five-year-old.

Every year I have several students who are academically advanced but who are socially and emotionally immature. In some cases very immature. One of the defining characteristics of gifted is “asynchronous development.” Gifted students are out of the norm in terms of their development when compared to their age peers. That can mean they are out of the norm in more than just the realm of intellect. Which is why you can have a fifth grader working at the intellectual level of a 15-year-old but acting emotionally like a five-year-old. My first year in education, I worked as a Paraeducator in a Designed Instruction classroom. At the time, I didn’t know how deeply that experience would impact my practice as a classroom teacher. I spent one year in that DI classroom. In that time, I instructed students one-to-one on reading and life-skills, and also worked with the whole class to build a boat, to learn independent living through grocery shopping and cooking, and also coached the Special Olympics basketball team. These were amazing experiences and sparked my initial interest in becoming a certified teacher, but the most important impact came from how the lead teacher worked with our team. I didn’t know how much his actions affected me until I took a position in which I worked in concert with others and realized how much I had learned from him.

My first year in education, I worked as a Paraeducator in a Designed Instruction classroom. At the time, I didn’t know how deeply that experience would impact my practice as a classroom teacher. I spent one year in that DI classroom. In that time, I instructed students one-to-one on reading and life-skills, and also worked with the whole class to build a boat, to learn independent living through grocery shopping and cooking, and also coached the Special Olympics basketball team. These were amazing experiences and sparked my initial interest in becoming a certified teacher, but the most important impact came from how the lead teacher worked with our team. I didn’t know how much his actions affected me until I took a position in which I worked in concert with others and realized how much I had learned from him.