I keep trying to put down the topic of technology in the classroom, and I keep finding it impossible. Last week two things arrived in my inbox.

The first is a short article summarizing decade long research comparing reading comprehension from a screen with comprehension from paper. The conclusions were unambiguous: reading from screens harms comprehension compared to reading from paper. This is one of the first articles I’ve read in some time offering such clear conclusions:

“More evidence is in: Reading from screens harms comprehension.”

“One likely reason: Readers using screens tend to think they’re processing and understanding texts better then they actually are.”

Virginia Clinton, heading up the study says, “Reading from screens had a negative effect on reading performance relative to paper.”

and,

“There is legitimate concern that reading on paper may be better in terms of performance and efficiency.”

Reading this threw me back into memory. Sitting in the Henier auditorium, at the community college where I work part time, listening to a recent PhD graduate from the University of Washington (forgive me for forgetting her name), report her research findings on reading comprehension and technology. Her findings seemed contradictory to me. She reported finding that young readers reading from iPads comprehended the content at similar levels but were slower in reporting it because they were interested in describing the technology.

For example, if a student read a paper copy of a picture book and was asked comprehension questions they immediately discussed the content. If a student read the same picture book from an iPad and was asked the same comprehension questions, they discussed what buttons they pressed, and the interactions with technology before they discussed content. The researcher presenting dismissed the delay, but it stood out as alarming to me. As a parent and as a teacher efficiency is important to me. My top rules for technology in my personal life and in my classrooms are:

- It must add to life

- It must not distract from life

Last month I wrote about the history of character education in American schools and drilled down to the character traits and values the

Last month I wrote about the history of character education in American schools and drilled down to the character traits and values the

How many times have you groaned about sitting through professional development? How do you feel about a parade of presenters telling you yet another way you can do your job? Do you get excited about trainings? About conferences? About the newest in education-related publications?

How many times have you groaned about sitting through professional development? How do you feel about a parade of presenters telling you yet another way you can do your job? Do you get excited about trainings? About conferences? About the newest in education-related publications? “Yes, and…”, also referred to as “Yes, and…” thinking, is a rule-of-thumb in improvisational comedy that suggests that a participant should accept what another participant has stated (“yes”) and then expand on that line of thinking (“and”). It is also used in business and other organizations as a principle that improves the effectiveness of the brainstorming process, fosters effective communication, and encourages the free sharing of ideas.” (For a good article that explains it more fully along with videos, go

“Yes, and…”, also referred to as “Yes, and…” thinking, is a rule-of-thumb in improvisational comedy that suggests that a participant should accept what another participant has stated (“yes”) and then expand on that line of thinking (“and”). It is also used in business and other organizations as a principle that improves the effectiveness of the brainstorming process, fosters effective communication, and encourages the free sharing of ideas.” (For a good article that explains it more fully along with videos, go

Shameless plug time: There is an amazing learning opportunity on our horizon. The Washington Teachers Advisory Council is hosting their third conference next month. This conference takes place at beautiful Cedarbrook Lodge in Seatac on May 4th and 5th. Lodging included, it will cost you only $100-125 to attend, which is a steal! At this conference, you will encounter an all-star lineup of presenters, panelists, and speakers, including 2019 WA Teacher of the Year Robert Hand and 2018 National Teacher of the Year Mandy Manning. Sessions will include topics like transforming special education inclusion practices, educating to advocate, innovating education with STEAM, social emotional learning and character education, and much more.

Shameless plug time: There is an amazing learning opportunity on our horizon. The Washington Teachers Advisory Council is hosting their third conference next month. This conference takes place at beautiful Cedarbrook Lodge in Seatac on May 4th and 5th. Lodging included, it will cost you only $100-125 to attend, which is a steal! At this conference, you will encounter an all-star lineup of presenters, panelists, and speakers, including 2019 WA Teacher of the Year Robert Hand and 2018 National Teacher of the Year Mandy Manning. Sessions will include topics like transforming special education inclusion practices, educating to advocate, innovating education with STEAM, social emotional learning and character education, and much more.

It takes a little knowledge to dig a little deeper sometimes. This month, I am hitting the knowledge. Next month – I am digging a little deeper. What am I talking about? Character education! Let’s first get a little history…

It takes a little knowledge to dig a little deeper sometimes. This month, I am hitting the knowledge. Next month – I am digging a little deeper. What am I talking about? Character education! Let’s first get a little history… The minute my mom was diagnosed, a quarantine poster was slapped on the front door of their house. When her dad came home from work, he wasn’t allowed inside his own home. That’s how seriously they took quarantines in 1938.

The minute my mom was diagnosed, a quarantine poster was slapped on the front door of their house. When her dad came home from work, he wasn’t allowed inside his own home. That’s how seriously they took quarantines in 1938.

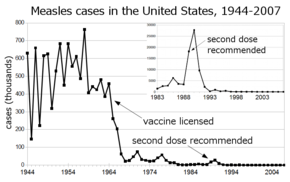

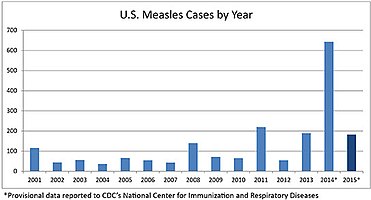

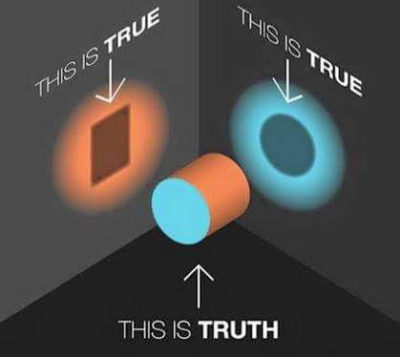

Which is truth?

Which is truth?