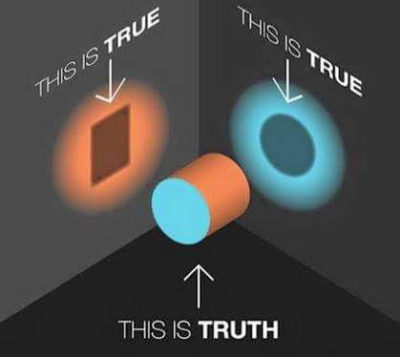

Which is truth?

Which is truth?

“Those that know, do. Those that understand, teach.”-Aristotle

“Keep up that fight, bring it to your schools. You don’t have to be indoctrinated by these loser teachers that are trying to sell you on socialism from birth.” –Donald Trump Jr.

Both statements make me think of my students. I think of the hundreds of times I have been asked what I think about a topic. I think of the hundreds of time I have smiled in response and said, “I am far more interested in you finding out what you believe and why you believe it…”

You see, I firmly believe educators should remain neutral in the classroom when it comes to controversial or political debates; an absolute beige-on-tan kind of neutral.

That type of neutral takes immense self-control and an intense belief in the importance of the role I play in my students’ lives. I truly do believe students can and do look up to teachers. A good teacher influences their students’ lives far beyond the standardized test scores they earn at the end of the year. My beliefs could easily become my students’ beliefs. That is not a dynamic of educating young minds that I take lightly.

So, why do I do it? Why do I withhold my deepest beliefs from my students if they may take them on and, in my opinion, make this world a better place? Continue reading

Imagine that you are that armed teacher. Maybe you have hours of target shooting. Maybe you hunt. Maybe you are very comfortable with your weapon.

Imagine that you are that armed teacher. Maybe you have hours of target shooting. Maybe you hunt. Maybe you are very comfortable with your weapon. Trauma is a beast with multiple personalities. It can slink in the classroom, with downcast eyes and arms crossed; hoping to be unseen. It can also fling itself through the door, announcing its energy in bubbly, overly helpful behaviors that cross the border frequently into bossy and inflexible, resulting in a lonely child bewildered by her lack of friends. Trauma can be tired, unfocused, quick to be red-faced angry, fidgety and/or slack-bodied. All within a single day! Trauma is exhausting and confusing, not only for children, but for teachers too. That is why I am thrilled that our state is taking a proactive approach to helping BOTH teachers and students to address many of the behaviors that students of trauma present with in our classrooms.

Trauma is a beast with multiple personalities. It can slink in the classroom, with downcast eyes and arms crossed; hoping to be unseen. It can also fling itself through the door, announcing its energy in bubbly, overly helpful behaviors that cross the border frequently into bossy and inflexible, resulting in a lonely child bewildered by her lack of friends. Trauma can be tired, unfocused, quick to be red-faced angry, fidgety and/or slack-bodied. All within a single day! Trauma is exhausting and confusing, not only for children, but for teachers too. That is why I am thrilled that our state is taking a proactive approach to helping BOTH teachers and students to address many of the behaviors that students of trauma present with in our classrooms.

We use a variety of terms to describe geographic areas in our school community. Upriver is a pretty common term used to describe the area due east of our community that parallels the Lewis River. I first heard this term when I started teaching in the district. When we received our first yearly snow, I was told that the kids who live upriver needed to go home. I didn’t really understand but later, during the summer, I went hiking and discovered that upriver includes a significant elevation gain that approaches the Gifford Pinchot National Forest and Mt. St. Helens. The bottoms is another area I’ve often heard students reference. I really had no sense of where that was nor did I ever find myself in a position to go explore the area. I’d ask and folks would point in a direction but it never made much sense to me. There was talk amongst staff that students would go hang out by the bottoms. I also knew that some of my students lived over there (wherever it was). I came to learn that this area is close to the Columbia River. There are a few parks down there and a road that runs along it that seems a bit too narrow for driving high speeds. It’s also host to some local farms and farm families.

We use a variety of terms to describe geographic areas in our school community. Upriver is a pretty common term used to describe the area due east of our community that parallels the Lewis River. I first heard this term when I started teaching in the district. When we received our first yearly snow, I was told that the kids who live upriver needed to go home. I didn’t really understand but later, during the summer, I went hiking and discovered that upriver includes a significant elevation gain that approaches the Gifford Pinchot National Forest and Mt. St. Helens. The bottoms is another area I’ve often heard students reference. I really had no sense of where that was nor did I ever find myself in a position to go explore the area. I’d ask and folks would point in a direction but it never made much sense to me. There was talk amongst staff that students would go hang out by the bottoms. I also knew that some of my students lived over there (wherever it was). I came to learn that this area is close to the Columbia River. There are a few parks down there and a road that runs along it that seems a bit too narrow for driving high speeds. It’s also host to some local farms and farm families.  The new year is upon us, happening too fast, as usual. Just as we get used to the schedule of a Winter Break, we are trying to get a mountain of tasks done before school starts up in a few short days. Where does the time go?

The new year is upon us, happening too fast, as usual. Just as we get used to the schedule of a Winter Break, we are trying to get a mountain of tasks done before school starts up in a few short days. Where does the time go? As I write this, my home is filled with the savory aroma of black-eyed peas, collard greens, and pork. It’s a tradition in our family, and in many places around the country, to eat black-eyed peas on New Year’s. It’s for luck and prosperity in the new year.

As I write this, my home is filled with the savory aroma of black-eyed peas, collard greens, and pork. It’s a tradition in our family, and in many places around the country, to eat black-eyed peas on New Year’s. It’s for luck and prosperity in the new year.  Don’t get me wrong; we need all of the supports mentioned in the proposal. We need more counselors in our buildings. We need plans for school safety that are actionable. We need all educational personnel to be trained to recognize and respond to symptoms of emotional distress. But, does anyone take time to wonder how we could prevent getting to the point where we are responding to distress?

Don’t get me wrong; we need all of the supports mentioned in the proposal. We need more counselors in our buildings. We need plans for school safety that are actionable. We need all educational personnel to be trained to recognize and respond to symptoms of emotional distress. But, does anyone take time to wonder how we could prevent getting to the point where we are responding to distress?

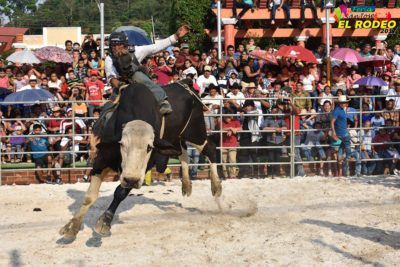

My New Year’s resolution is to not find myself on a bull ride with a student. In bull riding, an eight second ride earns the intrepid rider a spot on the scoreboard. It is intense and tough to do. In teaching, eight seconds can earn your student a chance at learning and you a chance at teaching.

My New Year’s resolution is to not find myself on a bull ride with a student. In bull riding, an eight second ride earns the intrepid rider a spot on the scoreboard. It is intense and tough to do. In teaching, eight seconds can earn your student a chance at learning and you a chance at teaching.