For me, summertime = reading time.

During the school year, I can’t keep up with the growing stacks of books precariously balanced on my nightstand. So in the summer, I set a goal of reading 5-10 books. My pattern is consistent—usually some young adult fiction to add to my classroom library (All American Boys, Ms. Marvel Vol 1), something political (Evicted), something I meant to read ages ago (Crazy Rich Asians trilogy, Orange is the New Black), a friend recommendation (Number One Chinese Restaurant), a “teacher” book (I’ll read that one mid-August), a book I only half-finished years ago (Whistling Vivaldi) and a mindless beach read (Matchmaking for Beginners, Girl Logic).

Despite burying myself in non-school related books, I don’t stop thinking about the work. I know, I know. Like many teachers, even when I’m “off”, I’m still on. No matter how much I try to avoid thinking about my classroom and my students (even with my mindless, beach reads), my mind wanders back. When I read, I imagine faces of students who would ____. I mull over ways I could use a certain chapter in my unit on ___. After years, I’ve finally accepted that reading and reflecting during the summer is part of my “self-care” plan.

And so this summer, I met 2014 Ms. Marvel, a Pakistani-American, Muslim teenage girl struggling to balance faith, family, and friends. I deepened my understanding of the American housing crisis and how evictions disproportionately impact Black women. I ruminated on the meaning of love and how to express it to those closest to me. I reflected on the meaning of identity threat, and how stigmatization directly impacts student success in my classroom.

Summertime is also prime travel time. My husband and I make it a priority to grab our passports and get out of town. The magic of travel is that it literally transports you to a different world. Eating Korean BBQ on South Tacoma Way or ordering Tom Kha in East Tacoma is not quite enough to understand what it means to be Korean or Thai. Breathing Bangkok air, sitting in Kuala Lumper traffic, visiting the S-21 Genocide Museum in Phnom Penh puts you face-to-face with people, culture, and history in a new way.

Both the acts of reading about and physically traveling to another world, always refreshes my perspective. I might arrive with preconceived notions about a certain group or culture based on my previous experience or my hours scouring a Lonely Planet guidebook and TripAdvisor pages. But I always leave with a greater understanding of systems, an empathy for human struggle, and a realignment of my own values with what actually matters. Mark Twain once said, “Travel is fatal to prejudice, bigotry, and narrow-mindedness.” This is the main reason I continue to get out of dodge each summer and sweet-talk my friends into going abroad. For students, there are more complications than simply applying for a passport and buying a ticket to Beijing.

Literacy experts use the phrase Windows & Mirrors when referring to the way a reader engages with a book. This concept was actually developed by Dr. Rudine Bishop in her essay Mirrors, Windows, and Sliding Glass Doors. Essentially, a book can help you see yourself, your family, your community or your values (mirror). A text might serve as a window, peeking into someone else’s life and learning about another world. Finally, a novel could work as a sliding door–at first giving you a peak into another realm, then sliding open so you can walk through it (think Butler or Tolkien). I’ve made it a reading habit to ask myself is this text meant to be a mirror, a window, or a sliding glass door? For whom? As a reader, I want mirrors to feel a sense of personal validation (that’s easy for me to find since I’m a white female). As a reader and an educator I know I need more windows and sliding doors in my life to help me be a better teacher.

And so this summer, I once again remember that while I still believe everyone should travel abroad, I know not everyone can. As the new school year approaches, I accept my responsibility as a teacher to construct classroom experiences that transport students to new worlds, even for a few days. Besides showing pictures and sharing stories, I can make instructional choices such as incorporating more diverse texts as mainstream curriculum. We must intentionally find windows, mirrors, and sliding doors for each learner.

“Mommy made me mash my M&M’s,” trills from the nervous troupe of twenty-five on the stage. Kindergarten to high school, these children are all warming up their voices for this summer’s presentation of “Alice in Wonderland” to be presented at our community theater. It is an all-children production; children will be acting, building sets, running lights and generally spending their summer months of June and July busily learning the art of theater. Wow! It is a whirlwind of creativity and intense focus!

“Mommy made me mash my M&M’s,” trills from the nervous troupe of twenty-five on the stage. Kindergarten to high school, these children are all warming up their voices for this summer’s presentation of “Alice in Wonderland” to be presented at our community theater. It is an all-children production; children will be acting, building sets, running lights and generally spending their summer months of June and July busily learning the art of theater. Wow! It is a whirlwind of creativity and intense focus! The Office of the Superintendent of Public Instruction recently convened a task force for the purpose of expanding

The Office of the Superintendent of Public Instruction recently convened a task force for the purpose of expanding  One program in particular, though, serves as a model for the potential outcomes of successfully implementing dual language throughout a school –

One program in particular, though, serves as a model for the potential outcomes of successfully implementing dual language throughout a school –  I had the pleasure of meeting the pre-school teacher, Celia Butler. She is from Columbia. Her passion was clear from the moment I walked into her classroom and her connection with her students was inspiring. She greeted her students in English and in Spanish and had a room rich in color and in language. Each tiny student who came in, greeted their teacher with “Good Morning” and a hug. There was love in her classroom – an uplifting community to get them started on there journey through school. This classroom is representative of all the classrooms in this school. This in and of itself shows the community and engagement in a dual language environment.

I had the pleasure of meeting the pre-school teacher, Celia Butler. She is from Columbia. Her passion was clear from the moment I walked into her classroom and her connection with her students was inspiring. She greeted her students in English and in Spanish and had a room rich in color and in language. Each tiny student who came in, greeted their teacher with “Good Morning” and a hug. There was love in her classroom – an uplifting community to get them started on there journey through school. This classroom is representative of all the classrooms in this school. This in and of itself shows the community and engagement in a dual language environment.

So what is this “bushel basket” all about? It’s from the New Testament. In the King James version Matthew 5:15 says, “Neither do men light a candle, and put it under a bushel, but on a candlestick; and it giveth light unto all that are in the house.” Now, historically, a bushel was a container for goods, such as grain, that became a unit of measure. So this is a bit weird in modern terms. But you get the idea. In this context, the light could be your faith, but it can also be your wisdom, your learning, your spark. Why hide a light?

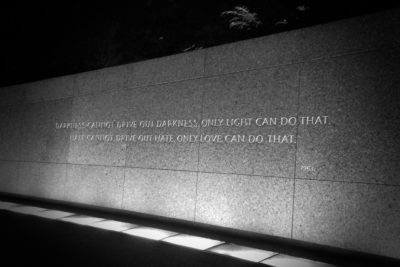

So what is this “bushel basket” all about? It’s from the New Testament. In the King James version Matthew 5:15 says, “Neither do men light a candle, and put it under a bushel, but on a candlestick; and it giveth light unto all that are in the house.” Now, historically, a bushel was a container for goods, such as grain, that became a unit of measure. So this is a bit weird in modern terms. But you get the idea. In this context, the light could be your faith, but it can also be your wisdom, your learning, your spark. Why hide a light? Now let me take this a step further. Where there is light, there is darkness. And let’s face it; there have been some dark moments in our schools recently. There are dark issues faced by our students and our colleagues. To fight the darkness, we need to rally behind the light. We teachers can do so much to help our students as they face the future, as they become the problem-solvers of tomorrow. As Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., famously said, “Darkness cannot drive out darkness; only light can do that. Hate cannot drive out hate; only love can do that.”

Now let me take this a step further. Where there is light, there is darkness. And let’s face it; there have been some dark moments in our schools recently. There are dark issues faced by our students and our colleagues. To fight the darkness, we need to rally behind the light. We teachers can do so much to help our students as they face the future, as they become the problem-solvers of tomorrow. As Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., famously said, “Darkness cannot drive out darkness; only light can do that. Hate cannot drive out hate; only love can do that.”