Teacher leadership requires us at times to buck the system. By this I mean that sometimes we will find ourselves in the minority on an issue, and we will be faced with tough decisions. Should we go with the opinion of the majority, or do we stick to what we feel to be right? How do you know that you are on the side of what is right?

In this business, we have a solid and predictable compass on our leadership journey. What is best for the students informs all that we do. The needs of the students drive our decisions because, if the students are failing to thrive, our system is failing. Often, teacher leaders become frustrated with administrations and other influential bodies that drive policy based on money, staffing issues, politics or other lesser things. It is then that we bristle and arm ourselves with research, data, and anecdotal evidence to march bravely to the front and speak on behalf of those who matter most, our students.

Teacher leaders take pride in representing our students. Still, when we find ourslelves faced with yet another issue where we must raise our hand and our voice, where we must offer the better way, despite being “just” teachers, it can be challenging.

I’m currently struggling with such a dilemma. Our district is strenghtening its retention policy to discourage a rapid uptick in junior high students with failing grades. The majority of district staff believe that if our policy has more “teeth,” if we actually retain more students, then others will work harder. This issue strikes a very harsh chord with me, and it’s personal.

I’m currently struggling with such a dilemma. Our district is strenghtening its retention policy to discourage a rapid uptick in junior high students with failing grades. The majority of district staff believe that if our policy has more “teeth,” if we actually retain more students, then others will work harder. This issue strikes a very harsh chord with me, and it’s personal.

My path to teaching has not been conventional. Many teachers come from middle class upbringing and school was a positive part of their young lives. For me, my childhood was marked by poverty, disfunction and abuse. Although, school, at times, was a sanctuary, in the end I chose to fail several classes in high school. I didn’t like or trust some teachers. My emotional needs took priority over academics at the time. Although I graduated on time, I let my grades fall and jeopardized my future. Punitive measures pushed me farther away from my teachers and my goals.

Fast forward to my adulthood, and the economic difficulties continued. I was a single mom with two children, struggling with poverty, homelessness, and general upheaval while I finished my education. My son failed fifth and sixth grades. His school wanted to retain him. Fortunately, the next school year I got my first teaching job, moved him across the state, and had him in my first seventh-grade class. He earned a D…from his mom. But, after settling in, he started to feel like the staff and the students cared about him. He started to appreciate his education and his own abilities. It was a complete turnaround. By the time he graduated, he had a B average.

So there is the anecdotal evidence, and the source of my personal passion. However, the research is vast that tells us that retention and other punitive measures do not work to improve engagement and achievement. (See links below)

But here is our real problem: Our student population is changing. We have a growing rate of poverty in our district. There are many students facing homelessness, abuse, neglect, disruption of every sort. Of course, we are already putting supports together for these troubled kids, but our resources are limited. And, we haven’t yet implemented the most basic changes to improve our outcomes: social-emotional learning curricula, trauma-informed teaching practices, remediation for low readers at the secondary level, peer mentoring, more frequent contact with adult mentors, etc. On top of that, they, the students, have not been asked what they need.

So, I ask, why are we getting “tough” on these kids before we get tough on ourselves? Our school generally supports the needs of its students. In fact, it is the same school that put my own son back on the path to success. However, missteps can be made. Teacher leaders should be ready to safeguard the needs of the students when and if they do.

Although I am as concerned as anyone else about the academic progress of my students, I believe that all students need emotional and academic support. I believe they need solid, trusting relationships with the adults in their school. I believe that they deserve a voice in the matter, too.

So, even though my position against retention is in the minority, I will stand by it, armed with data, case studies, and anecdotal evidence. I will listen to and consider the opposing views and share what I know and believe, hoping to make a difference.

As teacher leaders, we must regularly check our leadership compass. We must set our sights on true north–the academic and emotional needs of our students.

**************************************************************************

More reading about the retention issue, should you want to dig a bit deeper:

A quick psychologist’s point of view- “Does Student Retention Work?”

An older study that should have settled it- Flynn’s “The Effects of Grade Retention on Middle School Students’ Academic Achievement, School Adjustment and School Attendance”

A level-headed look at both sides of the issue- “Essential Questions Concerning Grade Retention”

Here is a link to a project that inspired me to bring my background in poverty into my teaching practice. Kristen Leong’s Roll Call Project illustrates the connections between students and their teachers. How are we different? What do we have in common? Does having something in common with our students matter?

And, for an alternative way of approaching students in poverty, check out the section on “Mind set” here- “Engaging Students with Poverty in Mind”

I teach middle school in the upper reaches of NE Washington. In our district, let’s just say there are a certain number of families where the belief is that Scientific Theories are “just theories…” and “scientist are always changing their minds on stuff – why should we believe in them at all?” Both of these widely held and openly expressed sentiments are easily corrected in my classroom with lessons on the definition of scientific theory and the nature of science being that of change. Yet, with the words, “My grandpa says you’re a liar. There is no climate change – it is just the weather,” blurted out from a freckle-faced middle-schooler ringing in my mind, it does not always feel a real easy space and place for the exploration of evolution, carbon footprints, and the beginning of a Universe based on physics.

I teach middle school in the upper reaches of NE Washington. In our district, let’s just say there are a certain number of families where the belief is that Scientific Theories are “just theories…” and “scientist are always changing their minds on stuff – why should we believe in them at all?” Both of these widely held and openly expressed sentiments are easily corrected in my classroom with lessons on the definition of scientific theory and the nature of science being that of change. Yet, with the words, “My grandpa says you’re a liar. There is no climate change – it is just the weather,” blurted out from a freckle-faced middle-schooler ringing in my mind, it does not always feel a real easy space and place for the exploration of evolution, carbon footprints, and the beginning of a Universe based on physics.

With all of my skepticism, there is one particular aspect of the Khan Lab School which I believe would benefit our most underserved students, and with careful planning, could be implemented in our public schools – the

With all of my skepticism, there is one particular aspect of the Khan Lab School which I believe would benefit our most underserved students, and with careful planning, could be implemented in our public schools – the

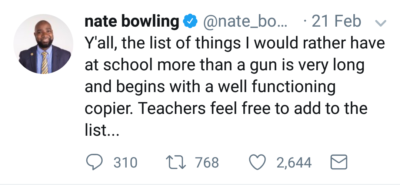

Always, there is a moment in February where teaching gets a little tougher. The slog of January has worn us down. Kids have been cooped up under the grey skies of a long winter, thirsty for sunshine and fresh air. Me? I am just tired. Tired of the same old tricks, same old excuses, same old everything from the same old students. Rinse. Repeat. Stuck in the February Funk.

Always, there is a moment in February where teaching gets a little tougher. The slog of January has worn us down. Kids have been cooped up under the grey skies of a long winter, thirsty for sunshine and fresh air. Me? I am just tired. Tired of the same old tricks, same old excuses, same old everything from the same old students. Rinse. Repeat. Stuck in the February Funk. All persuasive arguments begin with a story. That’s exactly what I was greeted with during my first “Teacher of the Year” school visit to

All persuasive arguments begin with a story. That’s exactly what I was greeted with during my first “Teacher of the Year” school visit to

Beyond the actual buildings, Oakesdale also lacks technology. The district currently contracts with the prison to purchase computers. Inmates refurbish the units, the district buys them at a minimal cost, then they add additional RAM and programs to make them usable. With the passing of their most recent capital levy, along with additional renovations, they plan to purchase Chromebooks for the high school. The computer science teacher is very excited.

Beyond the actual buildings, Oakesdale also lacks technology. The district currently contracts with the prison to purchase computers. Inmates refurbish the units, the district buys them at a minimal cost, then they add additional RAM and programs to make them usable. With the passing of their most recent capital levy, along with additional renovations, they plan to purchase Chromebooks for the high school. The computer science teacher is very excited. While Oakesdale is a great example of the challenges small rural districts face in remodeling and renovating their schools and in acquiring adequate technology (including access to high-speed wifi), it is also a great example of the benefits of a small community. Class sizes are small, and teachers really know ALL of their students. There is even a community calendar that highlights important dates for every member of the community down to anniversaries and birthdays. Individualized instruction is attainable and implemented. It’s also clear that Principal Dingman and the eductors are proud of their school and love to be there. It’s super cool to see.

While Oakesdale is a great example of the challenges small rural districts face in remodeling and renovating their schools and in acquiring adequate technology (including access to high-speed wifi), it is also a great example of the benefits of a small community. Class sizes are small, and teachers really know ALL of their students. There is even a community calendar that highlights important dates for every member of the community down to anniversaries and birthdays. Individualized instruction is attainable and implemented. It’s also clear that Principal Dingman and the eductors are proud of their school and love to be there. It’s super cool to see.