Last week my eighth graders presented their independent, interest-based projects, the culmination of two months of research and applied learning. Elizabeth showed us her original comic, which she published online. Maisy displayed her handmade quilt and told us about the history of quilting in America. Sam presented his Claymation short film. Dana taught us about installation art and demonstrated the infinity mirror she had made.

These projects were impressive examples of what students can do when they have access to the right resources. For Elizabeth, Maisy, Sam, and Dana, that meant high-speed access to specialized websites, including the publishing platform Webtoons.com, the Emporia State University archives, and the Seattle Art Museum’s website.

If the school’s broadband provider had blocked access to some of these sites because they don’t bring in money, if it had slowed the connection speed in order to provide other users with faster service, or if it had required the school district to pay extra for access to less lucrative sites, these and the other student projects would never have happened. And that bleak scenario is exactly what schools across the country are likely to face in the wake of the Federal Communication Commission’s (FCC’s) recent repeal of the practice known as Net Neutrality. Teachers and students will have fewer opportunities, and those with the fewest resources will, of course, suffer disproportionately.

What is Net Neutrality?

Since the internet’s inception, internet service providers have treated all content equally. They do not restrict, discriminate, or charge differently based on content, user, or type of device. This is the concept of net neutrality. In 2014 President Obama sought to ensure the continuation of net neutrality, and to that end asked the FCC to recategorize internet broadband service as a utility. The FCC followed this recommendation in February 2015, instituting regulations that prevented broadband companies such as Comcast, Verizon, and AT&T, from slowing or blocking access to legal websites, artificially slowing access for some customers while speeding it up for others, and charging customers extra for access to certain websites.

Net Neutrality in Schools

According to the 2017 State of the States report from the nonprofit EducationSuperHighway, 97% of Washington State’s school districts had the necessary fiber optic connectivity to meet the FCC minimum goal of 100 kpbs per student. At my school that means my colleagues and I can stream videos and download resources from YouCubed to help our students develop mathematical mindsets. This amazing website is helping us transform our practice. And we are not the only ones. As of this writing, YouCubed has received 22,895,390 visits. But what will happen if we can no longer freely access YouCubed or the countless other sites that support our teaching and our students’ learning? According to Richard Culatta, CEO of the International Society for Technology in Education, “when carriers can choose to prioritize paid content over freely available content, schools really are at risk.”

In high-poverty schools such as mine, the risk is especially great. The internet provides access to experiences that our schools could not otherwise provide, such as authentic science investigations and contact with project mentors. Many of our students also live in homes without reliable internet access; they depend on having it at school not only for their assignments, but to develop the technological literacy that all students need and deserve.

Net neutrality has helped to reduce inequities between well-funded and under-funded schools, between students of privilege and students of poverty. If such access disappears, the equity gap will increase.

Broadband service providers argue that net neutrality stifles the free market. Other opponents fear that regulation allows the government to invade our privacy. Those arguments do not persuade me. There is no financial incentive for broadband companies to provide unrestricted, high-speed access to consumers, including schools. If they have the opportunity to make money by restricting access to certain websites, or by charging consumers for access or faster service, they will do that in order to satisfy shareholders. We may well find ourselves living in a world that our students will recognize from their favorite dystopian novels: a world where access to information and expression exists only for individuals with the most power and the most money.

I asked my district’s chief technology officer if the district has a plan for how to respond to the effects of the repeal of net neutrality. He replied, “We had no impact before the change and from what I’m reading/seeing/hearing, the impact back may be just as little. This is a move to free market service, not the end of access. It’s high on my radar. I deal with the FCC almost monthly. I’m watching it.”

We all need to do more than watch. While there was no impact on schools before the net neutrality regulations, that does not mean broadband companies would not have moved in the direction of restricting access and speed. If we remain passive, if we wait to react until there is a change that harms schools, our students will lose.

For information on the efforts of various state leaders to ensure net neutrality in Washington State, go here.

I laid awake in bed at the Omni Shoreham. Light seeped through the cracks of the door and laughter drifted up from the courtyard. It wasn’t so much the time zone that kept me awake. I couldn’t turn my brain off. I often can’t turn my brain off.=

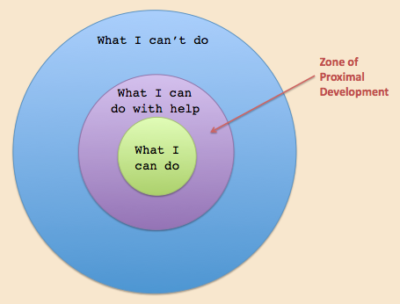

I laid awake in bed at the Omni Shoreham. Light seeped through the cracks of the door and laughter drifted up from the courtyard. It wasn’t so much the time zone that kept me awake. I couldn’t turn my brain off. I often can’t turn my brain off.= Think of putting fourth graders into first grade classrooms. That would be ludicrous, right? While the teacher is working with the first graders on “What I can do with help,” the fourth graders are well past the “What I can do” and into the “I’m bored and trying to amuse myself” zone.

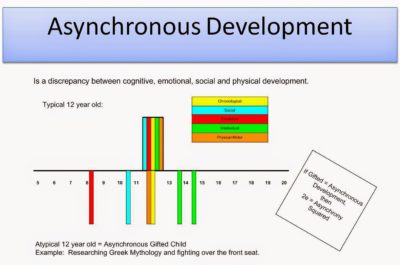

Think of putting fourth graders into first grade classrooms. That would be ludicrous, right? While the teacher is working with the first graders on “What I can do with help,” the fourth graders are well past the “What I can do” and into the “I’m bored and trying to amuse myself” zone. Every year I have several students who are academically advanced but who are socially and emotionally immature. In some cases very immature. One of the defining characteristics of gifted is “asynchronous development.” Gifted students are out of the norm in terms of their development when compared to their age peers. That can mean they are out of the norm in more than just the realm of intellect. Which is why you can have a fifth grader working at the intellectual level of a 15-year-old but acting emotionally like a five-year-old.

Every year I have several students who are academically advanced but who are socially and emotionally immature. In some cases very immature. One of the defining characteristics of gifted is “asynchronous development.” Gifted students are out of the norm in terms of their development when compared to their age peers. That can mean they are out of the norm in more than just the realm of intellect. Which is why you can have a fifth grader working at the intellectual level of a 15-year-old but acting emotionally like a five-year-old.