Like many parents across the nation, we received our children’s Smarter Balanced Assessment (SBA) results a few weeks ago. The results, printed in color ink, did not largely surprise us. What did, however, was our children’s reaction.

My daughter is now a 6th grader. She’s been taking this test for a few years, although science was a new component for her last year in 5th grade. In the past, she’s been worried about the adaptive portion of the exam, nervous about whether she’s moving too slow or too fast and wondering if her screen should look alike or different from her peers. One year, right before school let out for summer, we received notification that she was invited to attend a summer math program. This invitation was an opportunity for extended math instruction, which I was gladly willing to take her to. I did, however, have no sense that she was struggling in math. Her standards based report card always revealed that she was on target. So when I dug around a bit more and contacted the building assessment coordinator, we discovered that she met standard and that the invitation was an accident. However, the damage was done. She was downtrodden about her math skills and entered into the 5th grade believing that her skills weren’t where they needed to be (whatever that means). After receiving the official score report and looking at the data with her, I saw a noticeable difference in my child and how she thought of herself as a math student. Even then, it took her months and at least a quarter in 5th grade math before she felt confident about her skills and abilities. You’d think that I would have learned my lesson.

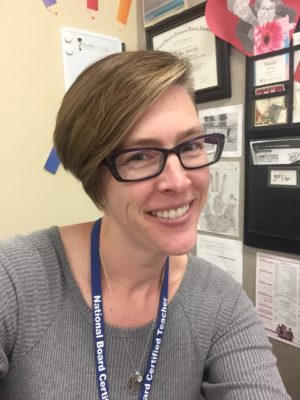

So this year when the assessment results arrived in the mail, I immediately opened them up. After reviewing the data, I decided to sit down with my children to discuss the results. My daughter the now 6th grader, looked at her scores and said, “I guess this means I’m pretty smart.” I was stunned. I’m thankful that I had enough clarity of thought to respond with, “Uh, this test doesn’t measure whether you’re smart. It tells you that you can answer specific questions related to certain skills and standards that the testing organization wants to measure. It certainly doesn’t address your ability to learn music.” My husband, her father, is a middle school band teacher. My daughter has been playing piano for five years (read: I’ve been paying for piano lessons for five years.) She nodded and walked away. I then sat down with my son to review his first SBA results.

But I wish I hadn’t. In fact, I’m done sitting down with my children to talk about these scores. Sadly, I think they, like so many other children, adults, school districts, and states, are defining themselves in relation to a score. My daughter’s self esteem as a math student was tied to that exam. This year, she used the exam to confirm a sense of self.

And that’s scary.

And unhealthy.

And it must stop.

I want to be clear. I’m not anti-test. I’m not anti Common Core. In fact, I embrace the Common Core, and I’d be happy to address that in another post. However, I fear that we’re sending a dangerous message to our youth if we oversell the data learned from the test. My school, like so many others, examined our scores in our back to school meeting. Thankfully, I didn’t get a sense that our students and our teachers were being overly celebrated or beat up due to assessment data. Our building elevates a variety of achievements, accomplishments, and talents. However, communities across the country put up gigantic signs on schools when some percentage of students are meeting a standard. This isn’t helping. We award schools for these scores and for the most growth over a year. I’m not saying it’s negative to give a hard working staff recognition for their efforts, but essentially aren’t we also celebrating the test score? What false sense does that give us of who our students are and what our students know and can do?

Do teachers walk around defining themselves by their evaluation score? I sure hope not. This would be an unhealthy approach to the profession, one that isn’t sustainable, and does not encourage self reflection or growth. So why do we do this with kids?

Let’s find other things to celebrate. Shouldn’t we consider exalting our students and our schools as more?