I just spent the day at Occupy Olympia. I carpooled down with three other teachers from North Kitsap, and we joined a group of teachers from around the state.

I just spent the day at Occupy Olympia. I carpooled down with three other teachers from North Kitsap, and we joined a group of teachers from around the state.

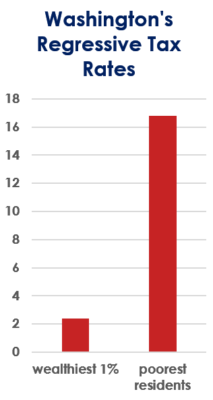

Before I left home, I read articles about Washington’s regressive tax system from newspapers in Seattle and Everett and Spokane. The key point they all make is that the top one percent of Washington wage earners pay only 2.4% of their income in taxes. In stark contrast, the poorest residents of the state pay 16.8%.

Honestly, there is a discrepancy between wealthy and poor across the nation, and it’s time to shine a spotlight on that fact nationwide. Meanwhile, though, the discrepancy in Washington is the worst. Washington has the most regressive tax system in the entire United States. (Not only is it a regressive tax system, it is also an oppressive tax system, especially to society’s most vulnerable.)

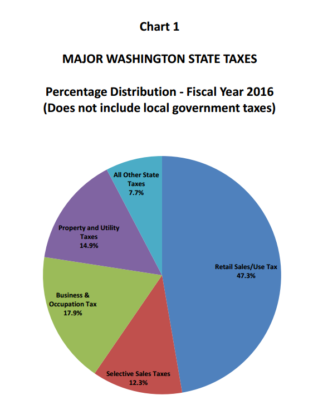

According to the Washington Department of Revenue website, Washington makes more than half its income from sales tax of one kind or another, which makes the state income especially vulnerable to fluctuations in the market. If the economy is tight, people don’t buy as much.

Face it, our sales taxes are high. Our gas taxes are high. Our B&O taxes are high.

No wonder whenever anyone raises the idea of any new tax—income tax, anyone?—people in Washington freak out. They panic.

I totally understand. If I had to continue paying the taxes I have to pay now AND I had to pay income taxes on top of that, my husband and I couldn’t afford to live in our three bedroom two bath house with our one car and a motorcycle and no pets. (Who can afford a dog anymore???)

It’s time to get creative.

So in Olympia I looked for people to talk to. I talked to the aide for one of my representatives. I spoke with representatives from other districts.

I said we needed more revenue in order to fully fund schools. But we couldn’t just add a new tax. In our state, that’s a non-starter.

I said we needed more revenue in order to fully fund schools. But we couldn’t just add a new tax. In our state, that’s a non-starter.

What we need is a complete tax overhaul from the ground up.

We need the legislature to come to the taxpayers and say, “Look, you will have lower sales taxes. Lower gas taxes. Lower B&O taxes. Lower taxes in general.

“At the same time we are going to implement an income tax for the most wealthy in the state.

“We are going to make taxes more equitable.

“And we will fully fund high-quality education throughout the state.”

One representative cheered. Another waved me off with “we can’t talk about that!”

One person asked how I would ever get the legislature to agree. I said it might take putting them all in seclusion—locking the doors and taking away their electronic devices until they had reached an agreement. Preferably unanimity. I said they could model the process on the US Constitutional Convention of 1787.

I also suggested watching the movie Separate But Equal to see how a sharply divided Supreme Court gradually moved to a unanimous decision on Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka in 1954.

So what happens if the legislature does it? What if they actually come up with a restructured tax plan that not only fully funds education but is equitable too?

I said obviously they would need to sell it to the public. We should go out in teams, legislators and teachers side by side, to educate and explain to the rest of the voters why this new plan makes sense.

If your school is anything like mine, you’re about to enter Testing Season. We come back from Spring Break, get reorganized and start gearing up for the SBAs. We review important material and have our students take practice tests on their computers. We teach test-taking strategies and emphasize the importance of sleep, diet and attendance.

If your school is anything like mine, you’re about to enter Testing Season. We come back from Spring Break, get reorganized and start gearing up for the SBAs. We review important material and have our students take practice tests on their computers. We teach test-taking strategies and emphasize the importance of sleep, diet and attendance.