Last month we had an incredible event. Nearly 100 NBCTs met to talk about how to preserve the National Board bonus in Washington State. My role was interesting; I got to monitor the conversations at seven different tables and glean the common, high-leverage ideas that emerged. What I learned was this:

Last month we had an incredible event. Nearly 100 NBCTs met to talk about how to preserve the National Board bonus in Washington State. My role was interesting; I got to monitor the conversations at seven different tables and glean the common, high-leverage ideas that emerged. What I learned was this:

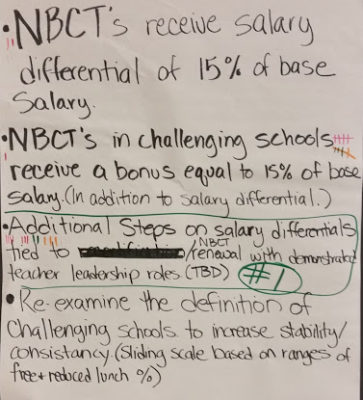

National Board Certified Teachers feel that the certification process has made them into better teachers. Many, if not most of them, were motivated to complete the process because of the bonus. Most, if not all of them, are convinced that the bonus is an important part of our state’s overall education system because of the impact that National Board Certification has on student learning. And finally, there was a broad consensus that the state should integrate the bonus into the Salary Allocation Model.

Making that happen is going to be difficult. First of all, this is probably the year when the Legislature tackles the McCleary Funding Issue. Suffice to say it’s going to be expensive, which means everything the state spends on schools will be looked at closely, including the NB bonus.

Furthermore, no one in Olympia has made any indication that they’re looking at significantly increasing revenue. A lack of increased revenue matters because the number of NBCTs has remained level since 2014, when the National Board revised its assessment process. Next year, however, the number of NBCTs could nearly double, depending on the success of the candidates who’ve been working through the new process. Our state is already spending upward of $50 million on NBCT bonuses; increasing that amount by 50 to 100% will give our lawmakers pause.

And finally, the Legislature that meets next month is not the Legislature that approved the $5000 bonus and the additional $5000 for teachers in high-needs schools. On average, state legislatures have about a 20% turnover whenever there’s an election, and there have been four elections since 2009. Should they decide to dump the bonus, there aren’t many lawmakers who would be killing a program they helped initiate.

So how do we go about convincing a bunch of lawmakers to spend an incredible and growing amount of money that doesn’t exist on a bonus they probably didn’t vote for in the first place?

Simple. You show them the standards that we, as NBCTs, met when we certified. You show them the standards and you tell them you met those standards. You tell them that going through National Board Certification helped you rise to that level. And then you give them examples of what you do every day in your classroom that illustrates how you embody those standards. The nice thing about the National Board Standards is that they’re written in the form of a description of an accomplished teacher. I don’t see how anyone who reads and understands those standards could look at a teacher who met those standard and deny them a $5000 bonus. I really don’t.

The only hard part is logistics. Somehow we need to get an NBCT and a set of standards in front of every lawmaker in Olympia for about an hour. It sounds complicated. But it also sounds important. It sounds like another incredible event.

Who’s in?

oy was still crushed. He had every reason to be. He had toiled long and hard cutting all the PVC pipe pieces for the original design—and for a small kid, it was laborious work. Clearly, he felt like all his effort was for nothing.

oy was still crushed. He had every reason to be. He had toiled long and hard cutting all the PVC pipe pieces for the original design—and for a small kid, it was laborious work. Clearly, he felt like all his effort was for nothing. I had plans for last Wednesday.

I had plans for last Wednesday.

I’ve been on more committees, task forces and planning teams than I care to remember. Many of them were productive and well worth my time. One particular team produced

I’ve been on more committees, task forces and planning teams than I care to remember. Many of them were productive and well worth my time. One particular team produced