This guest post is courtesy of Joanna Tovar Barnes. Joanna is a NBCT in EMC Literacy. She teaches third grade at Lydia Hawk Elementary in Lacey, WA. Her areas of professional interest include English Language Learners, social justice and integrating art, science and social studies into elementary curriculum. She facilitates for North Thurston School District’s National Board cohort. When not teaching Joanna travels the world seeking culture, food and understanding.

When I first heard my role at the Teach to Lead Summit in Long Beach, CA was a “critical friend” I wrinkled my nose and thought “that doesn’t sound like a good thing, who wants a critic?” The term ‘critical’ conjured up images of a group of reporters dissecting a starlet’s wardrobe choice or a food critic berating a chef for his uninspired appetizers. “The Critical Friend asks probing questions” the organizers of the event said, “They make suggestions about possible resources, and offer a fresh perspective on a problem.” I unwrinkled my nose a little and thought “Ok, maybe I can be a critical friend. I can do those things. That sounds helpful instead of scary. Also, maybe I need more of these ‘Critical friend’ people in my life.”

I think the opposite of a critical friend could be called an ‘echo-friend’. We all have them. You go to these friends when you want your conclusions validated, not questioned. When prompted they say things like “you’re absolutely right!”, “of course” and “obviously”. “I’m right and she’s wrong, right?” I ask “of course you are” my echo friend nods knowingly. I feel better. My own conclusions were echoed back to me and now I feel justified, reassured and comfortable. No questioning or suggestions, no discomfort.

Here’s the problem with the echo friend; eliciting this kind of feedback leaves us right back in the same place we started with our problem. In fact, now that our choices have been validated we are even more firmly rooted in the patterns that got us to our frustration point when we sought out our echo friend. I admit that sometimes I don’t want to go deep and think critically about big problems, I want to vent, or have someone tell me I’m right. However, I can’t be surprised when I still have the same problems with no new strategies to tackle them when I’m done with my echo-session. If I want to move forward in my problem solving I need a critical friend.

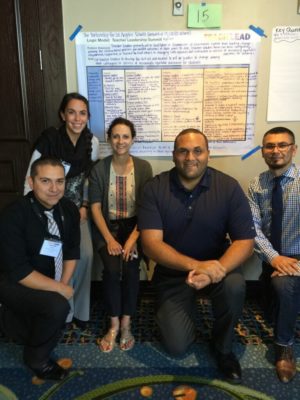

Teach to Lead Summit participants work together to process problems they face in their work. Teams and their critical friends use a logic model over two days to identify causes, outcomes and next steps.

From my time at Teach to Lead I am beginning to formulate some important steps in the art of being a critical friend. (it’s a good thing)

- A critical friendship begins with connection

Ok, we know that the critical part can help us move forward with a problem but that ‘friend’ word also really matters. As a teacher leader I’ve found that if people don’t know you and see you as a person outside of the current context they are less willing to accept critical feedback. People need to know that their critical friend is just that; friendly. That they assume positive intentions and competence and are there to be helpful.

I try to share something that tells people who I am professionally and personally. “I am passionate about social justice and interested in bilingual education” gives a quick glimpse into who I am at the core as a teacher and person. It makes me vulnerable and encourages the person I’m working with to do the same. I also present something I am still working to understand such as “I’m still learning about the new National Board component too, let’s look at the directions together”.

- Next it’s time to listen

The listen part is where the connection you built will allow you to get at what the problem is through how much the other person shares, which details they include and how they frame the problem. Without the connection you may not hear much, or you may hear only a small window into the problem at hand. You may need to go back and establish more of a connection before they will tell you more. Listening carefully will help you know which questions to ask. But hang on! There’s an important next step.

- Before questioning it is helpful to validate

Remember the echo friend we sometimes seek out? You’re going to want to meet that need too by acknowledging that this problem is frustrating, complex, etc. You can use some counseling 101 phrases like “That sounds really frustrating.” Or “There are a lot of different needs you’re having to think about.” This part matters because now you can strengthen your connection as a friend and you can meet their need to be validated. If we weren’t a critical friend we’d stop here. But here’s where the magic happens and we become something more than an echo friend. Here’s where we push our friend forward.

- Time to ask some questions

I know enough to know I know very little about the art of questioning. Luckily I have some awesome role models when it comes to this. Peers, friends and coaches who have challenged my thinking with thoughtful questions that at first made me huff, and then made me think much more meaningfully and deeply about something.

If you’re like me and are just starting to question critically maybe some sentence frames can help you. “I wonder…” “What if…” “Why do you think…” are some of my standbys because they’re open enough to allow the person wrestling with the problem to say something about them but encourage deeper investigation of one element of the problem.

- Now you can suggest resources

Oh boy, what you’ve been waiting for. Now you can tell them how to solve their problem if they would just…wait! Do not start telling them what you would do. This is not about you. (I can’t help it, it’s the bossy older sister in me) It’s about them and their problem. You can help by suggesting a resource you know of that might hold a missing piece of the puzzle, or someone who is struggling with a related problem. The suggestion part needs to be connected to what you heard initially and when you questioned. It’s important that the person you’re working with knows you’ve been hearing them when they shared.

Here’s the cool thing about the role of critical friend-you can do it with anyone starting right now! Just start connecting, listening, validating, questioning and suggesting. If you’re an echo friend already, you have a connection and must be someone they trust to listen. The next step for you will be questioning. I’ve pulled this trick on several people in my life since the Teach to Lead Summit.

I’m getting better at finding my own style of critical friendship and am recognizing when I see someone else who has mastered it and I seek them out to be one of my CFs. If we want to move forward in our understanding we need to embrace the discomfort of someone giving us more than an “uh-huh.” We all need more critical friends in our lives so we can become better educators and people. Isn’t that the point?

My amazing Teach to Lead Summit group who I served as a critical friend with our logic model.

Every National Board Certified Teacher has a story. This is mine.

Every National Board Certified Teacher has a story. This is mine.

In 1999 I was a relatively young National Board candidate. There were about 30 of us going through the process in our state, aspiring to join the seven or so Washington State NBCTs. Someone sponsored a reception in Seattle and then-governor Gary Locke was the featured speaker. While explaining his proposed 15% NBCT bonus, he remarked that someone in the Legislature asked him, “What if all of these candidates pass? How will we afford those bonuses?”

In 1999 I was a relatively young National Board candidate. There were about 30 of us going through the process in our state, aspiring to join the seven or so Washington State NBCTs. Someone sponsored a reception in Seattle and then-governor Gary Locke was the featured speaker. While explaining his proposed 15% NBCT bonus, he remarked that someone in the Legislature asked him, “What if all of these candidates pass? How will we afford those bonuses?”

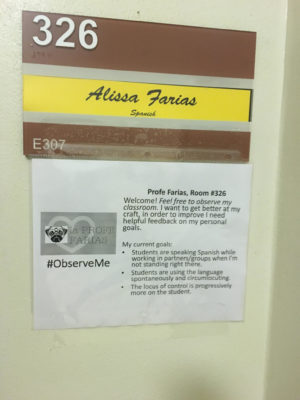

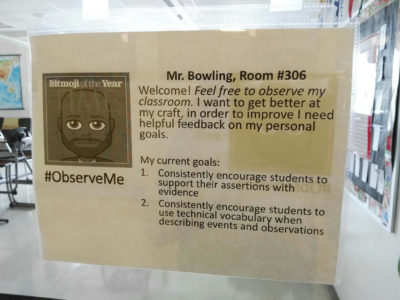

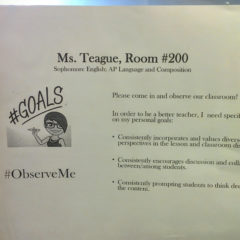

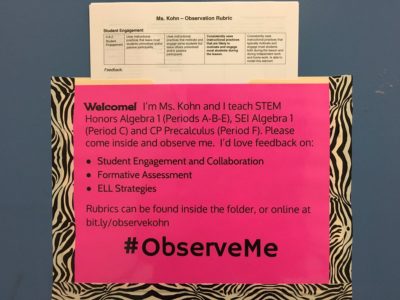

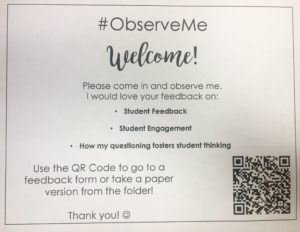

It forces me to have a growth mindset. If this sign is on my door, I am telling the world that I want to grow. I am inviting anyone to come in and comment on my instruct. Yeah, that’s a little scary. But it’s a healthy risk that models vulnerability and openness to others. Who could pop in? A visitor. A parent. The librarian. Another teacher on planning period. I’m both thrilled and terrified at the possibilities. The #ObserveMe challenge reminds us that teaching is relational and we need all types of perspectives to help us grow. This model is based on trust. By opening myself up to the community, I am making them a part of my learning process and saying that I value their voice in my growth.

It forces me to have a growth mindset. If this sign is on my door, I am telling the world that I want to grow. I am inviting anyone to come in and comment on my instruct. Yeah, that’s a little scary. But it’s a healthy risk that models vulnerability and openness to others. Who could pop in? A visitor. A parent. The librarian. Another teacher on planning period. I’m both thrilled and terrified at the possibilities. The #ObserveMe challenge reminds us that teaching is relational and we need all types of perspectives to help us grow. This model is based on trust. By opening myself up to the community, I am making them a part of my learning process and saying that I value their voice in my growth.