In southwest Washington, this is being referred to as a “Day of Action.”

I previously shared my struggle with this particular action, and when it came time for our local to vote, I spoke in opposition of the Walk Out and voted along with 34% of my local against it.

In a democratic system, though, the majority determines the course of action. My philosophical or political disagreement with the outcome of the vote does not grant me the right to disregard it.

Sure, I could choose to just sit at home and grade my seniors’ Othello tests: 17 short-answer questions from 60 students (just over 1000 individual responses) so even if I devote a generous 30 seconds per response, just grading and giving feedback on that one assignment alone is eight hours of work. That “action” on my part, though, doesn’t contribute to any kind of larger solution. It still has to get done, though… so looks like I’ll be tossing a bit less football with my sons. Such is the choice you make when you become a teacher. I knew that going in.

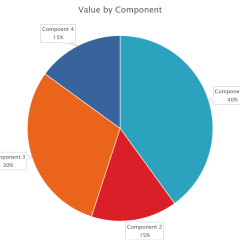

So back to this:

In a democratic system, the majority determines the course of action. My philosophical or political disagreement with the outcome of the vote does not grant me the right to disregard it.

This is the message I want to communicate to voters. In a democratic system, particularly one that permits voter-generated initiatives, the decision of the voters should be upheld. Philosophical or political disagreement does not grant one the right to disregard the voice of the voter. This disregard is what is happening within factions of our legislature, and this is what I will be protesting.

By Tom

By Tom