Teachers love telling stories.

These stories fit into three categories.

1) the “checkout-how-AHMAZING-my students-are-because-they-did/said/produced-this.”

See this incredible comic of the Great Depression? But did you READ this analysis of Hamlet by one of my IEP students?

2) the “listen-to-this-incredible-issue/idea- [insert name of awesome colleague]-and-I-had to-address-the-problem-with _____ [insert problem that keeps you awake at night].”

So I tried that strategy you suggested and increased my homework turn in rate from 75% to 95%!

3) the “OMG-you-won’t-believe-what-this-student/parent/admin said/did!”

I woke up to this email…

Assessment data loves to tell stories too. The stories are a meaningful way to bring numbers and facts to life. Generally, there are three stories the data communicates. First, it tells us how students are meeting established standards. Second, it tells us how students are growing. Third, it tells us where instruction needs to be changed or modified.

In our current educational climate, the primary storytellers are politicians, ed reform groups, or other “experts” who want fixate on the first kind of story. They want to focus on high stakes summative, standardized assessments like End of Course Assessments and the Smarter Balanced Assessment. They want the data to tell us how students are meeting established standards. This story is what many stakeholders are using to drive federal and state policy, particularly changes in teacher evaluations. This is the second consecutive legislative term where significant effort has been made to include standardized test scores in teacher evaluations through legislation (SB 5748). While that bill is dead, the idea of using testing data as a part of teacher evals was a recently added to a professional learning bill being reviewed (HB 1345). It seems WA legislators are determined to include summative assessment data in the teacher quality discussion.

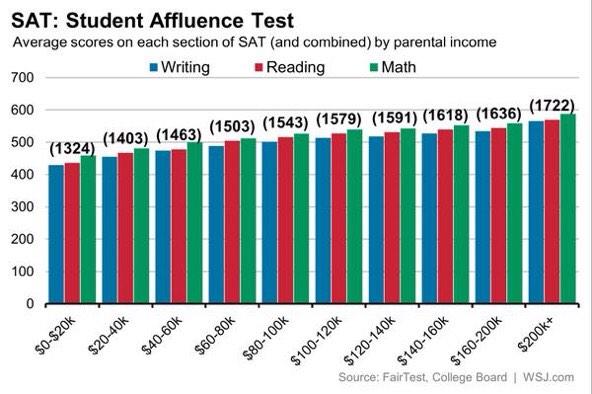

I believe that this fixation on just one type of data story (particularly spinning it to say “gotcha”) is why many teachers are up in arms. This is the concern that my fellow blogger, Spencer, addressed in his piece “How to Take An Arrow to Your Head”. Spencer captured this well by voicing how many teachers, myself included, recoil at the thought of using student test scores in their evals because it appears we are getting punished for factors beyond our control, such as systemic poverty, chronic absenteeism, and a host of other societal ills that negatively impact student achievement. Many teachers are fearful because the voices that dominate the discussion on assessments and “accountability” seem to have a myopic view that testing will remove bad teachers from classroom and focus the discussion on student achievement rather than student growth. In fact, last year I compared The Department of Education to the pigs in Animal Farm when I wrote about why teachers in this state could not accept the inclusion of test scores in their evals in order to save our NCLB waiver.

Another year of learning, reading, and thinking changed the way the legislature and some of my colleagues think and talk about assessment data. Examining the language of HB 1345’s amendment reveals this change. First, the idea of statewide assessments as being one of multiple measures. This means that there is more than one story being told and heard. From multiple viewpoints, we can truly get an accurate picture of how our students are growing in the classroom under the guidance of an effective teacher. The next important detail in the amendment is that “assessments must meet standards for being a valid and reliable tool for measuring student growth”. Standardized assessment have long been critiqued as invalid and unreliable. However, with the new CCSS assessment there is promise of rigorous testing that asks students to perform at a level necessary to be career and college ready. My friend Joe refers to it as the first “high-quality standardized tests” he has witnessed as far back as when he was in high school piloting the WASL. His hope, like mine, is that the current SBA assessment suite, although not by any means perfect, can provide one source (out of many) of data that can be used in meaningful conversations about teacher effectiveness, classroom instruction, and student growth.

By Tom

By Tom