Divided We Fall?

I’m sure there have been many times in history where it seemed like our country was irreconcilably divided. The Civil War is of course the ultimate example, with the Civil Rights movement closely following. But, all year, I have felt the strains of teaching in a cultural climate that seems both at odds with reality and finally aware of grim truths about our collective history.

I have students whose Google ID photos proudly ask to Make America Great Again , and others who display the light pink and blue flag that signifies their transgender identity. While there are always a wide range of opinions in the classroom, these differences between students feel more like cavernous divides.

There have been several points in the year, particularly around the presidential election, where I was a little glad I didn’t have students in class. Glad, at least, that I was the only one who had to read the vitriolic message from a student asking why we have to read about the sanctity of Black lives. Glad I could shield my students of color from his anger and unkind words that were rooted in fear, rather than empathy.

As a teacher, the line between what is political and what’s appropriate in the classroom is blurry at best. And, when we are all bombarded with media from every angle and avenue, it seems impossible to combat disinformation.

I’ve always found that teaching media literacy and critical consumption of media is important, but this year, among vaccine skepticism, conspiracy theories about stolen elections, and claims of learning loss, these skills felt even more pressing. My job is not to teach my students what to think, but how.

So, this year, when I dove into media literacy and argument writing, I strove to bring the real world into the classroom. If I could prime students to at least pause and critically think about what they consumed, I’d call that a win.

A Picture is Worth 1,000 Words

One particularly poignant lesson my student teacher created was around the power of images and captions across different media.

We went over connotation and denotation, and she then presented examples of images with different captions. She asked students to see how the image and their understanding of it changed based on those differences.

For example, when students saw these two, several swore that she lightened the second photo because they noticed the brightness of the sun and trees, even though nothing but the caption changed.

While she created the above image for the purposes of our assignment, I saw and remembered myriad examples in the real world.

This summer, when protests for racial justice broke out across the country, I paid particular attention to Portland and Seattle where headlines diverged wildly. They were called everything from “Antifa mob” and “riot” to “peaceful demonstrations.” Without being there, it was hard to parse the truth. Some images depicted Portland burning, while others showed a wall of mourners, holding candles. Two wildly different reports of the same story, with two very different connotations, interpretations, and impacts.

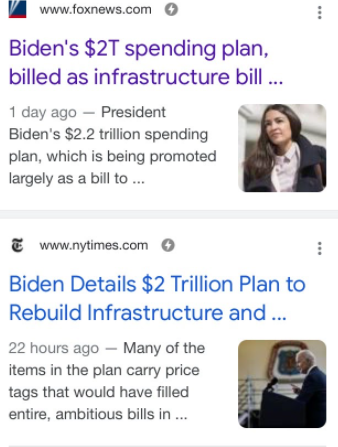

Then, as we were wrapping up our unit, Biden announced his two trillion dollar spending package, and two different news organizations posted very different accompanying photos. One of Biden, the president, and one of Alexandria Occasio Cortez, even though she wasn’t involved in the legislation and openly said that it was “not nearly enough.” Why, then, was she included in the headline?

These and subsequent lessons on analyzing images helped students realize the persuasive power that lay in small choices that are far from arbitrary. Captions are short, so every word matters. And yes, a picture is worth a thousand words, and our increasingly shrinking collective attention spans, they might be the most important thing a viewer sees.

Read Between the Lines

While a caption on a forested trail might not be high stakes, the protests over racial injustice and government spending most certainly are. Students, like most media consumers, are so used to the near constant stream of information that they don’t often take a moment to pause and analyze what they’re seeing.

Honestly, it was only because I was teaching this unit that those different posts about the infrastructure bill caught my eye. We’re so used to being bombarded with content constantly that it’s hard to remember to stop and think.

After completing this unit, and her research on defining the police, one student told me she realized the issue was much more nuanced than what she had seen on social media. She went into her research against the movement, but ended up doing her project in favor of defunding.

As with many well meaning, surface level media consumers, she understood the issue to be a false dilemma between police state or mass chaos, and she was actually fairly shocked when she learned more details.

I don’t want my students to become cynical, but I do want them to recognize when they are being sold a bill of goods. I want them to understand how words and images intentionally play together to convince a specific audience. I hope these lessons at least helped them think twice.

And, amidst rampant misinformation, fears, and theories around COVID vaccinations, I’d like to run an adult refresher course too, while I’m at it.