Tumwater Thunderbirds

In early 2021, the Washington legislature passed House Bill 1356 banning the use of native mascots in public schools.

Tumwater High School, where I’ve taught the past five years, has the logo of the Thunderbird and sits on Nisqually land, at the intersections of Cowlitz, Coast Salish, and Squaxin lands.

Part of the bill, aiming to build relationships between the tribes and school districts, specifies that mascots can be used, but only through consultation with and approval by the nearest tribe. So, when it passed, our school board formally met with the Nisqually tribe to discuss and reevaluate our use of the Thunderbird.

The most used mascot is what our admin affectionately calls “the fat chicken,” which has no visible ties to its native heritage. But, walk our hallways and you’ll find various nods to native art, including a questionable totem-esque logo and letterhead.

As one especially observant incoming freshman said in passing during summer school, “The amount of cultural appropriation in this school is astonishing.”

With several high profile public team changes, like The Washington Team, this student, and the members of our THS Social Equity Club are well versed in the inappropriate use of native mascots. They are more than willing to have tough conversations and explore necessary changes.

A student leader of the Social Equity Club, THS senior Sophia Ruiz explained the significance of the bill; “We are ever growing and changing, we need to honor the heritage that stems from the Thunderbird.”

However, alumni grumbled (“tradition” and all), and I was more than a little worried about backlash to the law. Righting wrongs isn’t usually comfortable and Tumwater has its fair share of negative press around equity work.

Don’t Forget the Water

On December 16th, a new era of the Thunderbird, one honoring it’s Nisqually heritage, was born.

Board members, district leaders, administrators, teachers, and student representatives were invited to the Nisqually Tribal Center for their official council meeting granting us use of the Thunderbird.

As the advisor for the student Social Equity Club, I was able to accompany my students to this historic day.

Willie Frank III, Chairman of the Nisqually tribe, who has played an integral role working with Thurston county schools around this issue, thanked us all for being there and said the chambers had never been so full. He shared the legend of the Thunderbird and its significance in the area at the base of Mt Rainier.

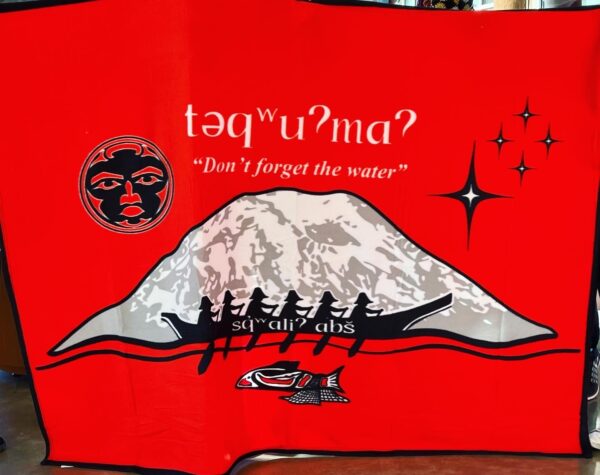

He explained the story of Teqwu? Ma? (“Don’t forget the water” in English) and wrapped two students in blankets with Mt.Rainier and that saying to signify our continued relationship.

Sophia was one of the students who was presented with a blanket, and I got goosebumps watching tears well up in her eyes.

“That day struck me as powerful and emotional,” she told me. “I was ecstatic that they were getting the recognition they deserve and were finally seen in the way they were always meant to be; important and beautiful.”

Our next steps as a school is to brainstorm ways to honor the Nisqually tribe and Thunderbird in more than just name and likeness. Should we say a land acknowledgement before every home game? Can we commission tribal artists to fill our spaces? Is our social studies curriculum inclusive enough of native history of our region?

“I want the school to be socially appreciative, not appropriative,” Sophia said. “Their tradition and livelihoods are… unique and special and they deserve the utmost respect from those that still use the Thunderbird. They deserve respect from everyone regardless.”

I couldn’t agree more.