“If you could redesign schools, what would you do?”

That had to be the best, most intriguing question a job application form ever handed me. I keep going back to it and playing with it. Mandy Manning’s post brought it up again. If we could start from scratch, what would we do?

Here are some ideas I’ve had over the years.

First of all, we need a lot more recess—supervised but unstructured, free play recess. A 15-minute break in the morning, a half-hour break at lunch, and a 15-minute break in the afternoon. That’s an hour of physical activity for the kids every day, which is exactly what the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends. (Why do we stop recess at the end of elementary school? Do children suddenly stop needing physical activity or a mental break during the day?)

First of all, we need a lot more recess—supervised but unstructured, free play recess. A 15-minute break in the morning, a half-hour break at lunch, and a 15-minute break in the afternoon. That’s an hour of physical activity for the kids every day, which is exactly what the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends. (Why do we stop recess at the end of elementary school? Do children suddenly stop needing physical activity or a mental break during the day?)

Second, we need a lot more art and drama and creative problem solving (like maker spaces). Things we used to have that have gotten squeezed out. If we want to stay competitive in the global market, we need to keep the part of the American educational system that was unique and attractive—our ability to develop creative thinkers. Ironically, the more we try to emulate homogeneous school systems from other nations in order to increase our scores on international tests, the more we are going to lose our edge.

I’ll tell you what I mean. I had a teacher from Japan visit my classroom. She was stunned at how eagerly my fifth grade students offered to leap up and do presentations. She told me none of her students would ever volunteer to present in class. She was impressed with the quality of the presentations.

As the kids walked out to recess, she went over to a display on my wall and asked, “What’s this?”

“Bloom’s Taxonomy,” I said. “You know what it is.”

She had never heard of it. Not in any of her education courses. So I explained it to her.

She nodded thoughtfully and said, “In Japan, we do this,” pointing to Knowledge and Comprehension.

I said, “Well, of course, everyone starts there. You have to. But then you do these,” and I pointed to the rest.

She said, “No, we do these,” pointing again to Knowledge and Comprehension. And she taught high school.

By the time we were done talking, she wanted to come teach in America.

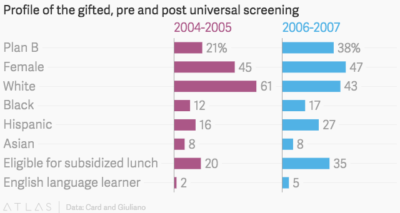

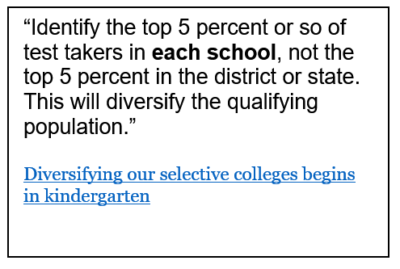

Universal screening eliminates the reliance on nominations/referrals (which eliminates any potential of bias or problems of access skewing the identification process).

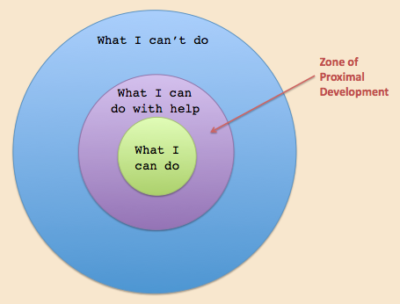

Universal screening eliminates the reliance on nominations/referrals (which eliminates any potential of bias or problems of access skewing the identification process). Think of putting fourth graders into first grade classrooms. That would be ludicrous, right? While the teacher is working with the first graders on “What I can do with help,” the fourth graders are well past the “What I can do” and into the “I’m bored and trying to amuse myself” zone.

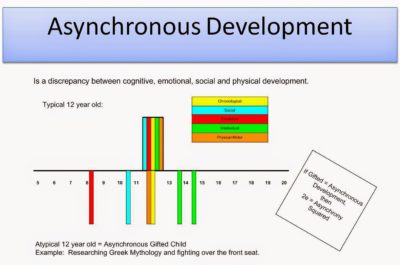

Think of putting fourth graders into first grade classrooms. That would be ludicrous, right? While the teacher is working with the first graders on “What I can do with help,” the fourth graders are well past the “What I can do” and into the “I’m bored and trying to amuse myself” zone. Every year I have several students who are academically advanced but who are socially and emotionally immature. In some cases very immature. One of the defining characteristics of gifted is “asynchronous development.” Gifted students are out of the norm in terms of their development when compared to their age peers. That can mean they are out of the norm in more than just the realm of intellect. Which is why you can have a fifth grader working at the intellectual level of a 15-year-old but acting emotionally like a five-year-old.

Every year I have several students who are academically advanced but who are socially and emotionally immature. In some cases very immature. One of the defining characteristics of gifted is “asynchronous development.” Gifted students are out of the norm in terms of their development when compared to their age peers. That can mean they are out of the norm in more than just the realm of intellect. Which is why you can have a fifth grader working at the intellectual level of a 15-year-old but acting emotionally like a five-year-old.

Other information we have is

Other information we have is

I just spent the day at Occupy Olympia. I carpooled down with three other teachers from North Kitsap, and we joined a group of teachers from around the state.

I just spent the day at Occupy Olympia. I carpooled down with three other teachers from North Kitsap, and we joined a group of teachers from around the state.

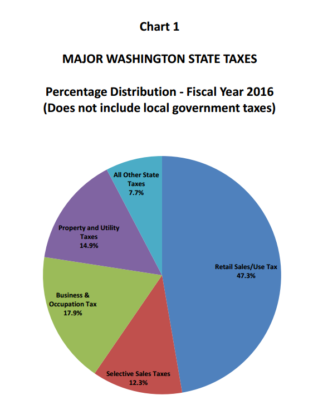

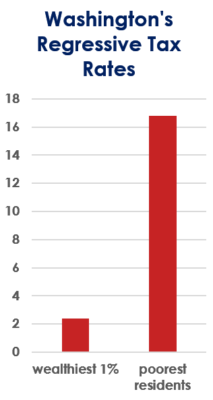

I said we needed more revenue in order to fully fund schools. But we couldn’t just add a new tax. In our state, that’s a non-starter.

I said we needed more revenue in order to fully fund schools. But we couldn’t just add a new tax. In our state, that’s a non-starter.