This week we celebrated fifth grade graduation. We had a drive-through event at the office building for our 100% on-line school. At the top of the driveway families turned in laptops and all the curriculum materials.

Then, with music playing and the bubble machine blowing, cars drove down the hill to the cheering teachers. We passed out balloons filled with confetti, bags of treats, and wristbands that read “I 100% survived 100% online school!”

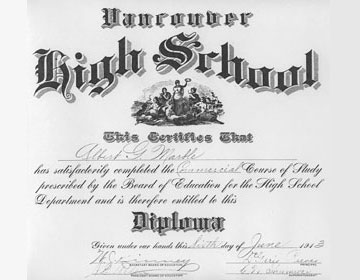

For each student we also handed out a graduation certificate. One line read, “You have successfully completed fifth grade.” I read that with each student and told them, “You are officially done with school. You don’t need to log into the system anymore.” That announcement led to a happy dance every time, the child in the car, me outside. “Freedom!” “Escape!” (in Finding Nemo fashion). “Hallelujah!”

Some students had their picture taken at the “Oh, the Places You’ll Go!” photo backdrop. Some said no thanks.

There were lots of smiles and even a few hugs.

I also spoke to every parent. Each time I said, “You did a great job.” The most common, instant reaction was physical. Shoulders fell. Heads dropped. Then the parent would say, “I thought I wasn’t doing well at all.” “I thought I was messing up.” “I thought I was failing.”

“No!” I said. “You were amazing! And you made it through this year. You did an awesome job.”

They straightened up then and starting talking about how hard it was.

“Yes. It was hard for everyone. I can’t imagine how you did it—

- you, with three other kids at home.”

- you, with a new baby.”

- you, with your husband deployed.”

Side note here—I had been telling parents all year what a terrific job they were doing. On that last day of school it was clear that they read my notes as general and applying to everyone else. Not to them. Individually, they each felt they were not doing well at all. Clearly, even phone calls hadn’t worked. All my encouragement during the year went nowhere. It wasn’t until I saw them face-to-face and spoke to them one-on-one that they actually believed me. Sigh.

Graduation was a thoroughly weird experience for all of us. It was the first time all year we got to see each other outside of Zoom. How strange was it? I didn’t recognize one of the other fifth grade teachers when I saw her in 3-D! She and I had met for PLCs nearly every day all year, but she looked different when she wasn’t flat.

One of the best things I heard that day was from one student’s mom who said it felt like I had reached through the computer and touched them. I told her it was mutual—we made a real connection in spite of the distance learning.

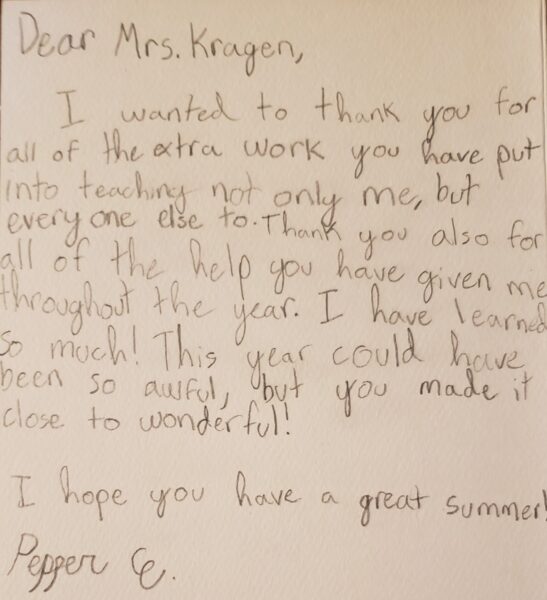

The other best thing was from a student who wrote in a card about how much she learned this year and added, “This year could have been so awful, but you made it close to wonderful!”

You know, I’ll take that. Close to wonderful is about the best I could hope for this year.

My take-away from all of this is that we must keep encouraging each other.

Encourage literally means put courage in.

- Put courage in students.

- Put courage in parents.

- Put courage in each other as teachers and staff.

Courage comes from cour, which means heart.

Discourage literally means to rip the heart out of someone.

Our job is to put heart in. So let me start.

It was a ridiculously hard year. You maybe felt like you were failing. You maybe felt like you couldn’t do it. You maybe felt like you were never going to make it.

But look at you. You are here!

And you learned things. Like how to persevere. Like how to stay engaged with people even when you can’t be with them physically. Like how to use more and more and more technology. (Right???)

And you made it.

You all did a great job this year.