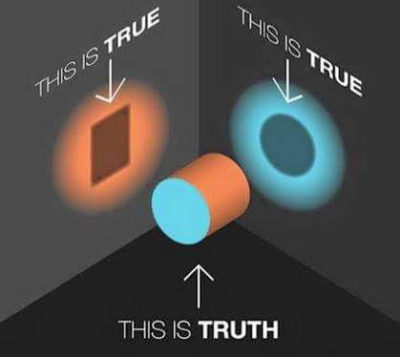

Which is truth?

Which is truth?

“Those that know, do. Those that understand, teach.”-Aristotle

“Keep up that fight, bring it to your schools. You don’t have to be indoctrinated by these loser teachers that are trying to sell you on socialism from birth.” –Donald Trump Jr.

Both statements make me think of my students. I think of the hundreds of times I have been asked what I think about a topic. I think of the hundreds of time I have smiled in response and said, “I am far more interested in you finding out what you believe and why you believe it…”

You see, I firmly believe educators should remain neutral in the classroom when it comes to controversial or political debates; an absolute beige-on-tan kind of neutral.

That type of neutral takes immense self-control and an intense belief in the importance of the role I play in my students’ lives. I truly do believe students can and do look up to teachers. A good teacher influences their students’ lives far beyond the standardized test scores they earn at the end of the year. My beliefs could easily become my students’ beliefs. That is not a dynamic of educating young minds that I take lightly.

So, why do I do it? Why do I withhold my deepest beliefs from my students if they may take them on and, in my opinion, make this world a better place? Continue reading

Don’t get me wrong; we need all of the supports mentioned in the proposal. We need more counselors in our buildings. We need plans for school safety that are actionable. We need all educational personnel to be trained to recognize and respond to symptoms of emotional distress. But, does anyone take time to wonder how we could prevent getting to the point where we are responding to distress?

Don’t get me wrong; we need all of the supports mentioned in the proposal. We need more counselors in our buildings. We need plans for school safety that are actionable. We need all educational personnel to be trained to recognize and respond to symptoms of emotional distress. But, does anyone take time to wonder how we could prevent getting to the point where we are responding to distress?

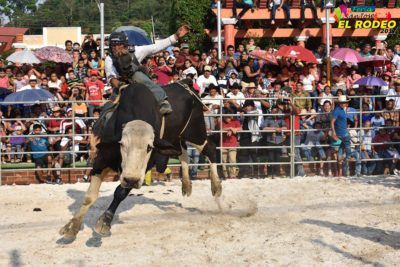

My New Year’s resolution is to not find myself on a bull ride with a student. In bull riding, an eight second ride earns the intrepid rider a spot on the scoreboard. It is intense and tough to do. In teaching, eight seconds can earn your student a chance at learning and you a chance at teaching.

My New Year’s resolution is to not find myself on a bull ride with a student. In bull riding, an eight second ride earns the intrepid rider a spot on the scoreboard. It is intense and tough to do. In teaching, eight seconds can earn your student a chance at learning and you a chance at teaching.

Oprah Winfrey often talks about the one thing every person truly wants; to be seen and to be heard. This makes sense and can impact your classroom when kept in mind while teaching. It turns out it can impact whole groups of people when applied to policy making.

Oprah Winfrey often talks about the one thing every person truly wants; to be seen and to be heard. This makes sense and can impact your classroom when kept in mind while teaching. It turns out it can impact whole groups of people when applied to policy making.