My district made a research-driven decision this year: We flip-flopped the start times of our elementary and secondary schools. Now, for the K-5 set, the bell rings at 8:00am (compared to last year’s 9:00am start) and for the secondary crew class starts around 8:45am (instead of an hour earlier).

Being a high school teacher and a morning person myself, I grudgingly accepted this shift to an almost 9:00am start (the day is practically half over by 9:00am!). I get the research all over the place about later start times for teens. The CDC has a page clearly stating their position, titled “Schools Start Too Early,” the New York Times Opinion page weighed in, and there is apparently a bunch of research supporting the premise that teens need to sleep in later.

Try as I might to find research to pile behind my confirmation bias, all I could seem to find were arguments that kids will “just stay up later” or that earlier start times leave room in the evenings for extracurriculars or jobs. Alas, no research at all that earlier start times can actually benefit kids.

So the problem I face now is the long stretch after lunch, and the reality that the time when kids are tired (from having just eaten) or wired (from having just eaten) is a greater proportion of my and my students’ day than it used to be. Granted, back in the olden days of last year when students had to rise so early for first period, there was the struggle of managing the bright-eyed-and-bushy-tailed and the faces-on-the-desks-and-drooling in the same classroom just as I now face the dichotomy of postlunch tired and wired.

This new after-lunch slog just feels different, though. It’s probably me (reminder: morning person) but after-lunch-learning looks a whole lot different than before-lunch-learning.

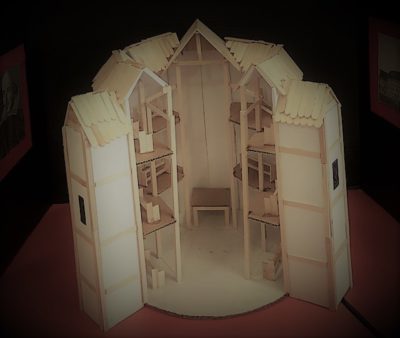

“Mommy made me mash my M&M’s,” trills from the nervous troupe of twenty-five on the stage. Kindergarten to high school, these children are all warming up their voices for this summer’s presentation of “Alice in Wonderland” to be presented at our community theater. It is an all-children production; children will be acting, building sets, running lights and generally spending their summer months of June and July busily learning the art of theater. Wow! It is a whirlwind of creativity and intense focus!

“Mommy made me mash my M&M’s,” trills from the nervous troupe of twenty-five on the stage. Kindergarten to high school, these children are all warming up their voices for this summer’s presentation of “Alice in Wonderland” to be presented at our community theater. It is an all-children production; children will be acting, building sets, running lights and generally spending their summer months of June and July busily learning the art of theater. Wow! It is a whirlwind of creativity and intense focus!

So what is this “bushel basket” all about? It’s from the New Testament. In the King James version Matthew 5:15 says, “Neither do men light a candle, and put it under a bushel, but on a candlestick; and it giveth light unto all that are in the house.” Now, historically, a bushel was a container for goods, such as grain, that became a unit of measure. So this is a bit weird in modern terms. But you get the idea. In this context, the light could be your faith, but it can also be your wisdom, your learning, your spark. Why hide a light?

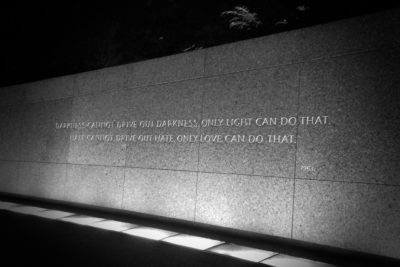

So what is this “bushel basket” all about? It’s from the New Testament. In the King James version Matthew 5:15 says, “Neither do men light a candle, and put it under a bushel, but on a candlestick; and it giveth light unto all that are in the house.” Now, historically, a bushel was a container for goods, such as grain, that became a unit of measure. So this is a bit weird in modern terms. But you get the idea. In this context, the light could be your faith, but it can also be your wisdom, your learning, your spark. Why hide a light? Now let me take this a step further. Where there is light, there is darkness. And let’s face it; there have been some dark moments in our schools recently. There are dark issues faced by our students and our colleagues. To fight the darkness, we need to rally behind the light. We teachers can do so much to help our students as they face the future, as they become the problem-solvers of tomorrow. As Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., famously said, “Darkness cannot drive out darkness; only light can do that. Hate cannot drive out hate; only love can do that.”

Now let me take this a step further. Where there is light, there is darkness. And let’s face it; there have been some dark moments in our schools recently. There are dark issues faced by our students and our colleagues. To fight the darkness, we need to rally behind the light. We teachers can do so much to help our students as they face the future, as they become the problem-solvers of tomorrow. As Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., famously said, “Darkness cannot drive out darkness; only light can do that. Hate cannot drive out hate; only love can do that.”