Tell me about your goals. What were they before Covid-19? What are they now?

I’m guessing they are somewhat different. Our priorities have shifted. At home, this is good – more time with family and pets, and far less time on our hair!

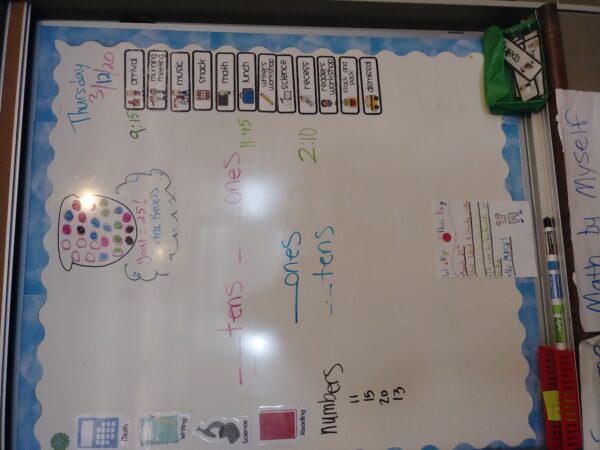

However, my educator goals have suffered terribly. Prior to this year, I had clear and powerful goals for my classroom, my students, and myself. In fact, I had three areas that I was independently researching or promoting, and I was really fired up about them, too. I was building a toolbox of my own to be the best teacher I could be to my students.

Here are my goals, pre-Covid:

Continue reading