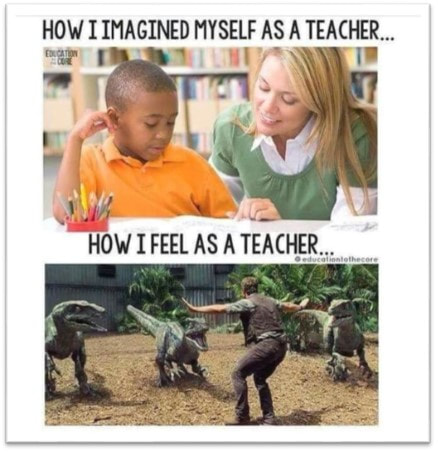

In December, I realized I was drowning. I was frequently getting sick, my class was spiraling out of control, and I would leave work so exhausted. I was facing overwhelming anxiety each day.

When everything is a mess, it’s hard to know where to start.

New teachers often find themselves in this position. It’s the position of not knowing what you don’t know. Looking back on my first year, it was incredibly hard to ask for help because it was impossible to pinpoint exactly what I needed.

Entering my second year I felt much more confident that I had it down, but as the months ticked by my classroom management began falling apart.

I reached out to one of my instructional coaches about what was happening in my classroom and she came in to observe a few times. While observing she never intervened, even when things got chaotic. We met a few days later to debrief. Surprisingly, she didn’t give me feedback on what she saw; instead, she just listened as I told her all of the things I felt were falling apart.

At the end of the conversation, she said to me, “You are the wrong kind of tired. You are exhausted because you spend your day putting out fires, not teaching. That’s called burnout and we are going to fix it.”