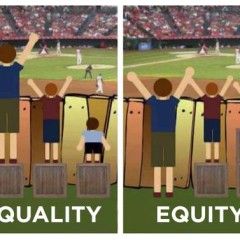

Seeing students for who they are and where they come from, as well as providing each student with an equitable distribution of educational supports or resources that allow the student to feel safe and secure, is social justice in education. In order for teachers to provide equitable educational opportunities, it’s important to become aware of each student’s background.

To be clear; this is not understanding how the student has done academically or behaviorally in their educational career, but truly knowing the student’s life circumstances outside of the classroom.

Getting to know students on the surface level is no longer enough. It doesn’t allow for an equitable classroom. It is important for teachers to create a methodical approach to getting to know their students as to not yield an inequitable or unconscious biased environment. Here’s a strategy I’ve found useful:

Continue reading

As an educator in a rural district, I have spent many years observing how our students often have less access to the options that are readily available in larger and urban districts. For instance, in addition to fewer electives, we offer few opportunities for students to take AP or dual credit courses, forcing many of our best scholars to travel forty miles to a community college as Running Start students. Additionally, where other districts had classes to support students who failed the state assessments in math or language arts, we did not have the resources or staff to offer such dedicated courses. Instead, because we are committed to our kids, our staff has worked outside of the regular schedule to support them and create Collections of Evidence or prep for test retakes.

As an educator in a rural district, I have spent many years observing how our students often have less access to the options that are readily available in larger and urban districts. For instance, in addition to fewer electives, we offer few opportunities for students to take AP or dual credit courses, forcing many of our best scholars to travel forty miles to a community college as Running Start students. Additionally, where other districts had classes to support students who failed the state assessments in math or language arts, we did not have the resources or staff to offer such dedicated courses. Instead, because we are committed to our kids, our staff has worked outside of the regular schedule to support them and create Collections of Evidence or prep for test retakes.