I teach middle school in the upper reaches of NE Washington. In our district, let’s just say there are a certain number of families where the belief is that Scientific Theories are “just theories…” and “scientist are always changing their minds on stuff – why should we believe in them at all?” Both of these widely held and openly expressed sentiments are easily corrected in my classroom with lessons on the definition of scientific theory and the nature of science being that of change. Yet, with the words, “My grandpa says you’re a liar. There is no climate change – it is just the weather,” blurted out from a freckle-faced middle-schooler ringing in my mind, it does not always feel a real easy space and place for the exploration of evolution, carbon footprints, and the beginning of a Universe based on physics.

I teach middle school in the upper reaches of NE Washington. In our district, let’s just say there are a certain number of families where the belief is that Scientific Theories are “just theories…” and “scientist are always changing their minds on stuff – why should we believe in them at all?” Both of these widely held and openly expressed sentiments are easily corrected in my classroom with lessons on the definition of scientific theory and the nature of science being that of change. Yet, with the words, “My grandpa says you’re a liar. There is no climate change – it is just the weather,” blurted out from a freckle-faced middle-schooler ringing in my mind, it does not always feel a real easy space and place for the exploration of evolution, carbon footprints, and the beginning of a Universe based on physics.

For a long time, I viewed my predicament of trying to teach the more politicized aspects of science education as just that…a predicament. I approached this quandary in a myriad of ways – mostly reflective of my own growth as a science educator. In my early years, I only briefly touched on the topics, hoping students would know just enough to do well on the test, but not place so much importance on them as to have students go home and start a discussion with their families on the topics…which would (egads!) become a conflict between myself and the parents.

Eventually, I realized that teaching biology without a deeper understanding of the adaptability of genetics over time, learning about climates without understanding the interplay between humans and our atmosphere, or never addressing the most mind-blowing question of, “What was here before what was here?” was hollow learning at best and a disservice to my students, my community and ultimately our nation as a whole at its worst. My students, all of our students, will be the next generation of voters deciding the fate of our populous; a fate more and more tied to a clear understanding of the sciences.

For these reasons, I am so very grateful and appreciative of both our state’s adoption of the Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS) and its continuing support of these standards. In a technical sense, these standards provide clear frameworks for teachers to know what they are expected to teach; the Theory of Evolution, Climate Change, the Big Bang Theory, and much more. The standards are well-crafted, with concepts building one upon another over the course of a K-12 education and resulting in a fact-based understanding of the Big Ideas of Science. All are threaded throughout by a need for inquiry-based learning and exploration of the topics; an eloquent design resulting in solid scientific literacy.

Not only that, but actual FUNDING is coming through the pipeline in support of full implementation of the standards in our state! For instance, our state’s 2018 budget has created Science Standards Pro Learning Funding, which provides grants to school districts and educational service districts to support professional learning in the Next Generation Science Standards. This funding is designed to be in direct support of training on climate change literacy.

Yet, the impact of these standards is far more powerful and subtle for many rural educators. These standards EMPOWER science teachers to teach science. In essence, I am not “choosing” to teach these topics to “ruin” the morals of children or divide the community, as per messages scribbled to me from a parent on a progress report. No, I am required to teach these topics and my feet are held to the fire to do so by Washington Comprehensive Assessment of Science. I can no longer shy away from the science topics I know may cause an issue because our school will be impacted by low tests scores. I simply must teach them.

It is out of my hands…and now in the minds of our next generation of citizens.

With all of my skepticism, there is one particular aspect of the Khan Lab School which I believe would benefit our most underserved students, and with careful planning, could be implemented in our public schools – the

With all of my skepticism, there is one particular aspect of the Khan Lab School which I believe would benefit our most underserved students, and with careful planning, could be implemented in our public schools – the

Always, there is a moment in February where teaching gets a little tougher. The slog of January has worn us down. Kids have been cooped up under the grey skies of a long winter, thirsty for sunshine and fresh air. Me? I am just tired. Tired of the same old tricks, same old excuses, same old everything from the same old students. Rinse. Repeat. Stuck in the February Funk.

Always, there is a moment in February where teaching gets a little tougher. The slog of January has worn us down. Kids have been cooped up under the grey skies of a long winter, thirsty for sunshine and fresh air. Me? I am just tired. Tired of the same old tricks, same old excuses, same old everything from the same old students. Rinse. Repeat. Stuck in the February Funk. All persuasive arguments begin with a story. That’s exactly what I was greeted with during my first “Teacher of the Year” school visit to

All persuasive arguments begin with a story. That’s exactly what I was greeted with during my first “Teacher of the Year” school visit to

Beyond the actual buildings, Oakesdale also lacks technology. The district currently contracts with the prison to purchase computers. Inmates refurbish the units, the district buys them at a minimal cost, then they add additional RAM and programs to make them usable. With the passing of their most recent capital levy, along with additional renovations, they plan to purchase Chromebooks for the high school. The computer science teacher is very excited.

Beyond the actual buildings, Oakesdale also lacks technology. The district currently contracts with the prison to purchase computers. Inmates refurbish the units, the district buys them at a minimal cost, then they add additional RAM and programs to make them usable. With the passing of their most recent capital levy, along with additional renovations, they plan to purchase Chromebooks for the high school. The computer science teacher is very excited. While Oakesdale is a great example of the challenges small rural districts face in remodeling and renovating their schools and in acquiring adequate technology (including access to high-speed wifi), it is also a great example of the benefits of a small community. Class sizes are small, and teachers really know ALL of their students. There is even a community calendar that highlights important dates for every member of the community down to anniversaries and birthdays. Individualized instruction is attainable and implemented. It’s also clear that Principal Dingman and the eductors are proud of their school and love to be there. It’s super cool to see.

While Oakesdale is a great example of the challenges small rural districts face in remodeling and renovating their schools and in acquiring adequate technology (including access to high-speed wifi), it is also a great example of the benefits of a small community. Class sizes are small, and teachers really know ALL of their students. There is even a community calendar that highlights important dates for every member of the community down to anniversaries and birthdays. Individualized instruction is attainable and implemented. It’s also clear that Principal Dingman and the eductors are proud of their school and love to be there. It’s super cool to see.

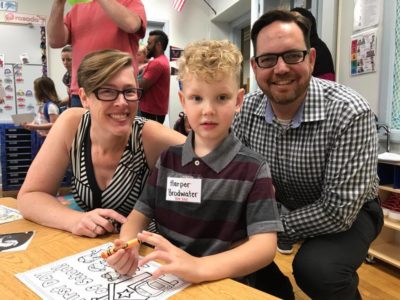

Two things you should know prior to reading this post: 1) I am writing through the lens of both a parent and a secondary educator (meaning I’m far from being an expert), and 2) my child has two amazing Kindergarten teachers. They are passionate and kind, they ensure my son loves school, and I can tell they care deeply about him. This is what every parent wants for their children. With these two admissions, I will proceed. I recently received two unsettling emails from my son’s teachers.

Two things you should know prior to reading this post: 1) I am writing through the lens of both a parent and a secondary educator (meaning I’m far from being an expert), and 2) my child has two amazing Kindergarten teachers. They are passionate and kind, they ensure my son loves school, and I can tell they care deeply about him. This is what every parent wants for their children. With these two admissions, I will proceed. I recently received two unsettling emails from my son’s teachers.