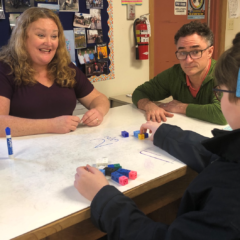

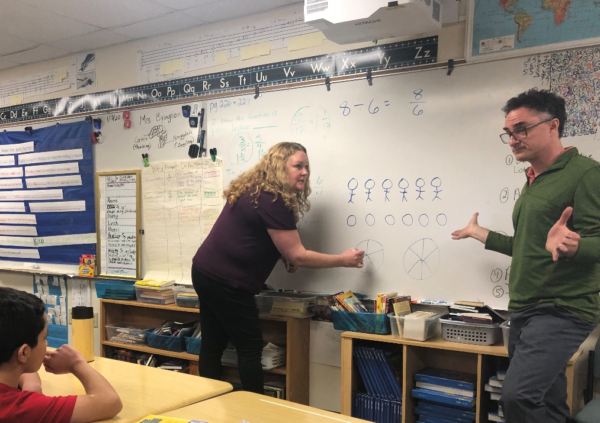

We sat in the thick of a heated discussion. Faced off in our groups of four, we discussed what approaches our schools would take in response to a student repeatedly refusing to comply with a teacher’s request to do their work. “We can’t expect the same level of behavior for all students. We need to be culturally responsive. Why push the issue? The kid isn’t really hurting anyone by not working.”

I sat back, mouth a gape. Did I just hear what I think I heard? And if I did, what does this mean for education? What does it mean for classroom culture? What does it mean for the future of our country? And no, that final question is not an exaggeration!

Not. Hurting. Anyone…?

Continue reading