On my journey to bring more diverse authors, stories and voices to my high school English curriculum, I notched a couple of wins in the last two weeks. (Quick recap, I’m seeking to add Tommy Orange’s 2018 novel There There to the 12th grade English curriculum.)

Win #1: The district Instructional Materials Committee will review my request. Okay, so this one is kind of like putting “Make to-do list” at the top of my to-do list just so I can check it off… I’m a member of this committee and have been talking up this book to anyone who will listen.

Win #2: My building secretary and principal worked some budget magic and found a way to fund two class sets of novels. My building is the smallest of the district’s three high schools, and two class sets will cover every 12th grader in my building over the coming months. (Of the other two buildings, one high school just recently opened and has not fully phased up to 9-12 enrollment and the other has a senior class typically in the 500s… so that’s a heavier lift.)

These two successes have made me think about what teacher leaders… particularly teacher leaders new to navigating systems… might need to be cognizant of in order to successfully advocate:

Continue reading

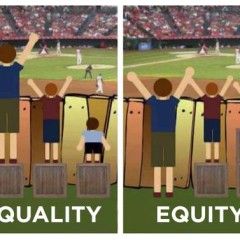

As an educator in a rural district, I have spent many years observing how our students often have less access to the options that are readily available in larger and urban districts. For instance, in addition to fewer electives, we offer few opportunities for students to take AP or dual credit courses, forcing many of our best scholars to travel forty miles to a community college as Running Start students. Additionally, where other districts had classes to support students who failed the state assessments in math or language arts, we did not have the resources or staff to offer such dedicated courses. Instead, because we are committed to our kids, our staff has worked outside of the regular schedule to support them and create Collections of Evidence or prep for test retakes.

As an educator in a rural district, I have spent many years observing how our students often have less access to the options that are readily available in larger and urban districts. For instance, in addition to fewer electives, we offer few opportunities for students to take AP or dual credit courses, forcing many of our best scholars to travel forty miles to a community college as Running Start students. Additionally, where other districts had classes to support students who failed the state assessments in math or language arts, we did not have the resources or staff to offer such dedicated courses. Instead, because we are committed to our kids, our staff has worked outside of the regular schedule to support them and create Collections of Evidence or prep for test retakes.