Last year my district bought a brand-new ELA curriculum for the elementary grades. It has short stories, poems, and even a handful of class sets of novels for teachers to share. There are also nonfiction materials integrated into the standard social studies and science topics of the different grade levels. For example, since fourth graders across America often study Native cultures, the fourth grade ELA curriculum has booklets about Native tribal history and a traditional Native story. In addition, there are booklets about money management, economics, and innovation. For science, the booklets include topics ranging from earthquakes, volcanoes, tsunamis, skeletons, and porpoises. There is also a short biography of an early paleontologist.

Our school day is scheduled around lunch, recesses, specialist time, a set period for math, a set period for reading, plus additional WIN times for math and reading—WIN standing for “What I Need,” whether it’s reteaching, extra support, or enrichment. Last year our fifth grade teachers complained that they had 20 minutes a day to fit in all the district-adopted science and social studies curriculum. “But you are teaching science and social studies in your ELA curriculum, right?” was the response they got.

Well yes. To a degree.

This week I attended a full-day curriculum workshop on the Next Generation Science Standards. The presenter at one point blurted out that he wished that one subject would be dropped from the school day altogether—reading.

Publishers would love to have you believe that they have provided the tools needed for integration by teaching science and social studies lessons within the ELA curriculum. But that’s exactly backwards for how true integration works.

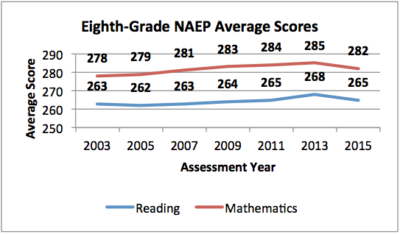

In fact, this backwards system of integration may explain why reading scores have flatlined since 1998!

In fact, this backwards system of integration may explain why reading scores have flatlined since 1998!

According to The Atlantic, “Daniel Willingham, a psychology professor at the University of Virginia … writes about the science behind reading comprehension. Willingham explained that whether or not readers understand a text depends far more on how much background knowledge and vocabulary they have relating to the topic than on how much they’ve practiced comprehension skills.”

The Thomas B. Fordham Institute says improving reading and writing instruction in America’s schools requires teachers taking the lead. “Teachers should tackle the content-knowledge deficit. In particular, they should take the lead in adopting content-rich curricula and organizing their lessons around well-constructed ‘text sets’ that help students build on their prior knowledge and learn new words more quickly.”

For real integration, I maintain that you need to start with your content-rich subject. Start with science. Or start with social studies. Figure out the main topics you will teach over the course of the year and decide how you will organize them. I teach either science or social studies, one at a time, alternating them. I am starting this year with Explorers and then Mixtures and Solutions. Next will be Colonies followed by Space. Finally we will study the Revolution and Constitution, and we will end the year with Living Systems.